Visavuori – Wikström’s Home and Studio

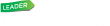

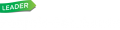

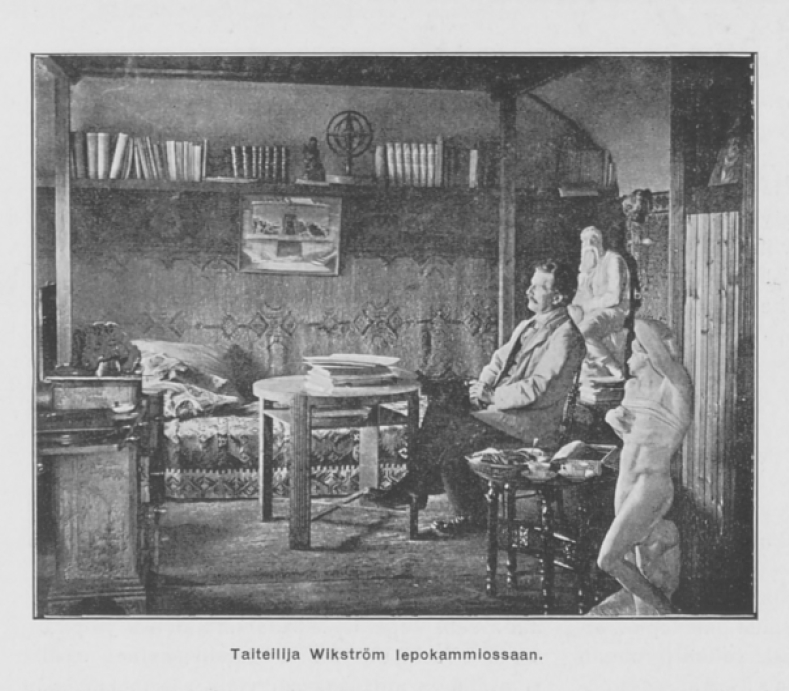

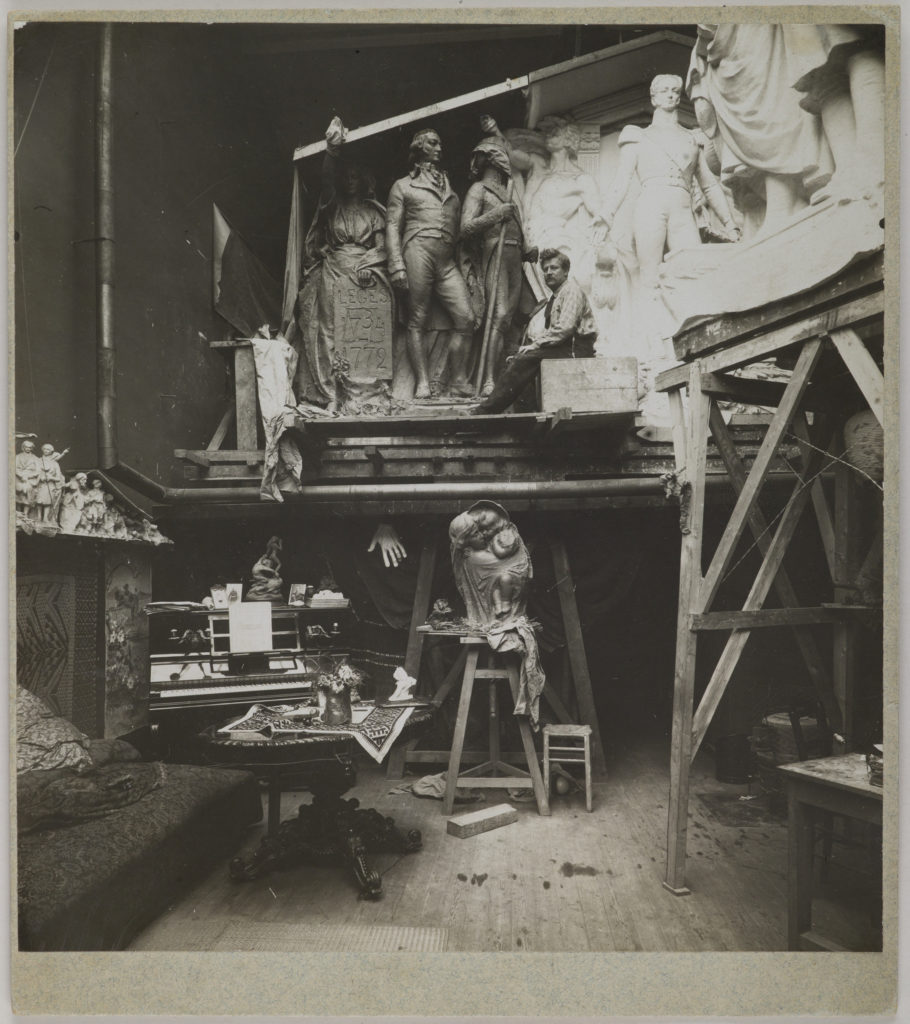

Emil Wikström lived in his home and studio Visavuori during five different decades. It is not only a central birthplace of his art, but also a work of art in itself – the complex, which Wikström designed with the help of his architect brother Akseli, has even been called ”his most beloved work of art”.

Wikström rented the lot of Visavuori for himself in 1893, and already the following year his new two-storied home and studio was completed there. This first Visavuori was made of wood, and, unfortunately, totally destroyed in a fire only two years later. Wikström lost almost all of his earthly possessions in the fire: furniture, drawings, papers and works, such as the unfinished frieze for the Säätytalo (House of estates) in Helsinki.

The planning of a new building was begun almost right away after the fire. During its construction Wikström and his family lived mostly in Paris, but he also visited the construction site from time to time to follow the progress of the work. In 1902 the house was ready for the Wikström family to move in. The next year, a separate atelier was built next to the living quarters, and a bronze foundry and an observatory were also installed there. A new western part, including a winter garden, an organ balcony and a library, was added to the atelier in 1912.

Wikström worked in Visavuori more or less continuously until 1918, after which he spent his summers there. Wikström’s last summer in Visavuori was in 1942, the year of his death, and since 1967 Visavuori has functioned as a museum dedicated to his life’s work. The museum’s collections include a version of all of the six hundred works by Wikström, and some of his works are also on display outside in the garden of Visavuori. These include, for example, the imposing bust of conductor Robert Kajanus (1856–1933).

The leading source of information about Visavuori in the net is its own page, where you can also find additional information about Wikström’s life and current exhibitions. There is also a virtual tour of Visavuori, which you can use to get acquainted with the premises from the comfort of your own home.

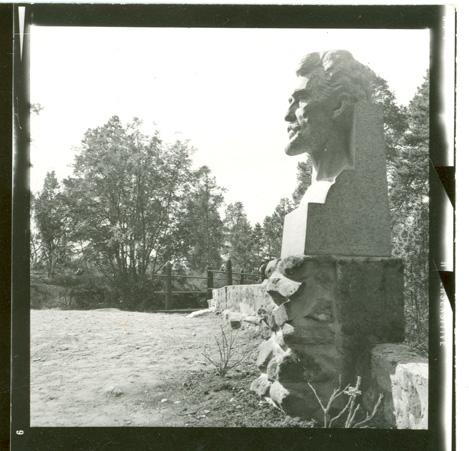

The Bust of Robert Kajanus

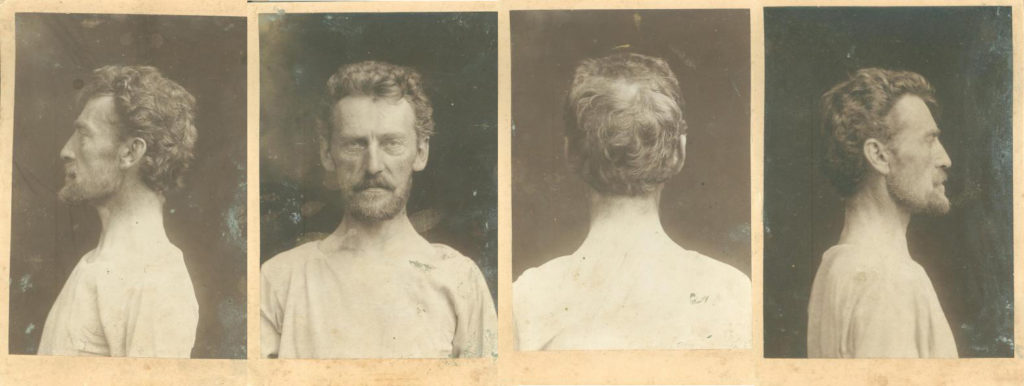

Conductor Robert Kajanus and Emil Wikström knew each other since the 1890s, and the classically handsome Kajanus became the subject of altogether three works by Wikström – a medal, a bust and a relief for Kajanus’s gravestone.

According to art historian Juha Ilvas, the story of how his bust ended up in its present place in the Visavuori garden goes all the way back to the so-called Art Palace, a building for music and visual arts that was planned in Helsinki in the early years of the 1900s. Ilvas writes that the bust was apparently linked to a plan the architect Eliel Saarinen had made for the building, and its backside suggests, that it was meant to be attached to the stone wall of the building’s facade.

The bust was completed in 1914, but the Art Palace -project never materialized. The sizable sculpture then became a bit of a nuisance for its creator, because it was hard to find a buyer or a suitable place for it. First it lay in Wikström’s atelier in Helsinki, from where it was moved to the Art Museum Ateneum in Helsinki around Kajanus’s 70th birthday. Seemingly, it was thought that the festivities might generate demand for the work, but this did not happen. Thus, the sculpture remained in Ateneum, where, according to Wikström’s son-in-law Yrjö Suomalainen, it ”lay for lenghts of time in dirt and dust under the staircase”.

Finally the bust had to be moved, and, according to Wikström’s biographer Mari Tossavainen, he decided to place it temporarily in Visavuori, even though it was ”heavy and expensive” and it felt ”so embarrasing” to bring it there. The artist really did not appreciate the work: son-in-law Suomalainen tells how Wikström packed it in a wooden box and left it to rot, turned over behind his atelier. According to Tossavainen, on the other hand, Wikström had said that as the backside of the sculpture was already carved nice and smooth, it could be buried ”nose down in the ground, so it might be used as a bench to sit on”. Apparently, it was the lack of demand that made Wikström so despise the work: perhaps the artist just wanted to forget the work, which had demanded much of his time, seemingly all for nothing.

Gradually the bust was lifted from its state of degradation, but not by Wikström. According to Yrjö Suomalainen, during the Winter War of 1939–40, soldiers moved it inside the atelier. Nowadays the work so frowned upon by Wikström is situated on the stone fence in the Visavuori garden, from where it solemnly watches over the visitors of Visavuori

Valkeakoski – The City of Wikström’s Sculptures

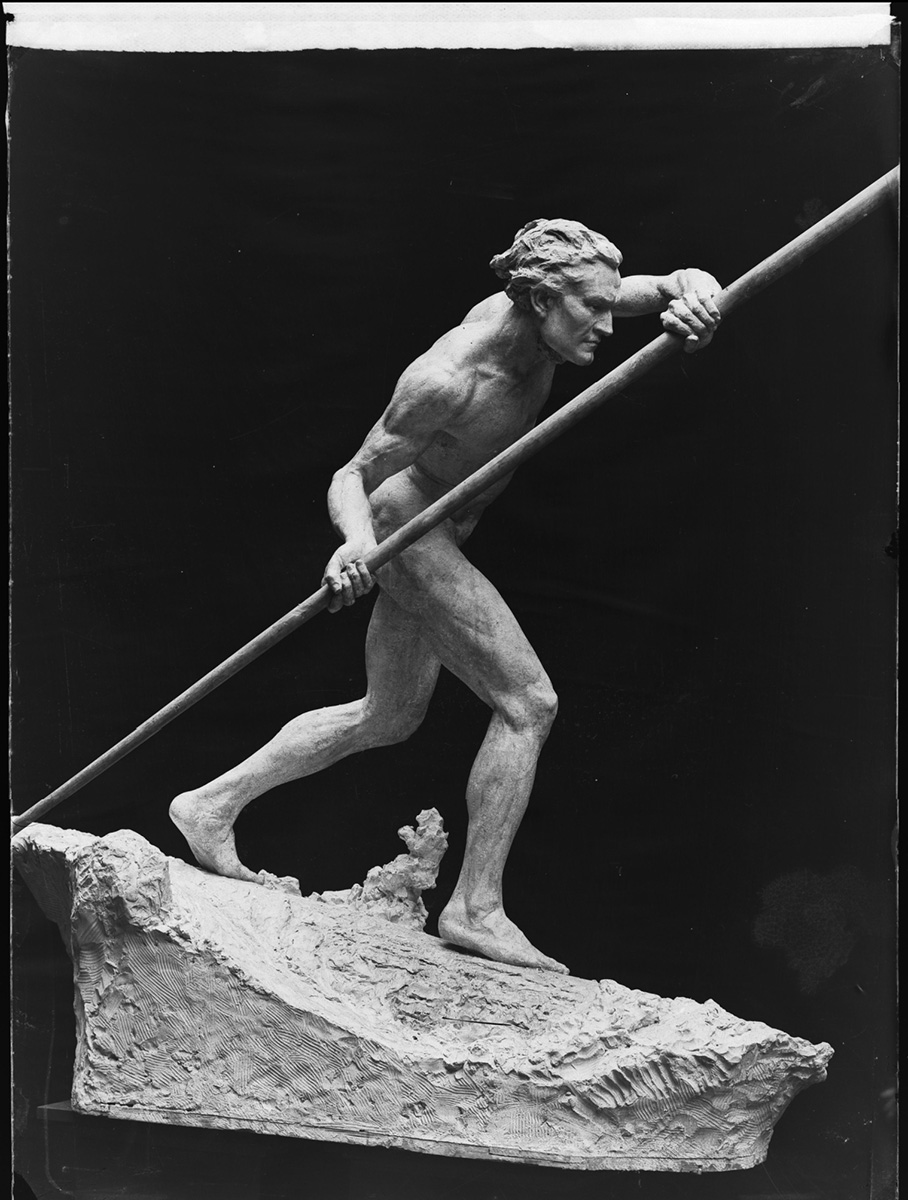

Near Visavuori lies another concentration of Wikström’s works – the city of Valkeakoski. Right in the city centre one can find Tukinuittaja (Koskenlaskija), Marjatta, Kuokkamies and Kalapoika (Onkipoika). A bit farther away in Päivölä Institute there is also Kokko, hauki ja Ilmarinen. A version of many of the works can be found in the Visavuori garden, too. The city of Valkeakoski has published a map in Google Maps, which you can use to find Wikström’s works. It also includes information and pictures of the sculptures. A map of the public statues and sculptures of Valkeakoski is also published in pdf-format.

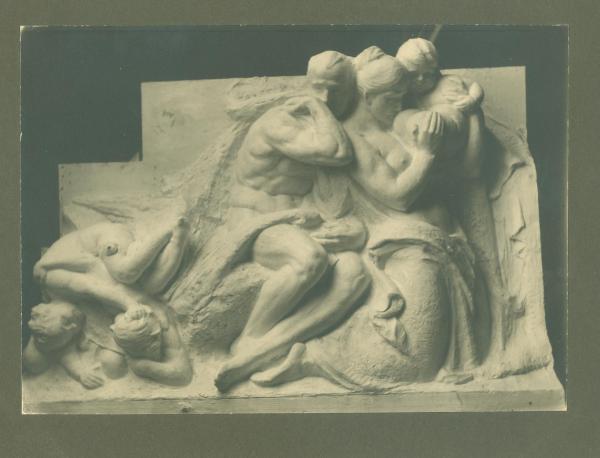

Marjatta

Marjatta, which derives its subject from the Kalevala, has a history as many-phased as the Kajanus bust. According to art historian Juha Ilvas, Wikström originally received a commission for a Marjatta-statue carved in marble from well known art sponsor Juho Lallukka in the summer of 1908, but for some reason the work did not materialize. In 1917 Lallukka’s widow Maria Lallukka renewed the commission, but at that time Wikström was unable to carry out the work for the set price due to a rise in expenses caused by fluctuating currency value. There was also another commission for the same work, but it was cancelled.

Eventually Marjatta was left, unfinished, in the hands of Wikström, who tried to offer it for acquisition to Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki. The sculpture, having gone through different phases of sketches and versions, was finalized in 1926, and like the bust of Kajanus, it was left in Visavuori. The bronze version of Marjatta situated in front of the Valkeakoski City Hall is from later times – it was unveiled in 1999.

According to Ilvas, the model for the face of Marjatta has been the same young woman, who also served as a model for the gravestone of Wladimir and Thyra Jurvelius discussed below. This unknown, mysteriously sad-looking woman has thus left a double imprint on the art of Wikström – and the history of Finnish sculpture, too. The body of Marjatta, again according to Ilvas, is modelled after another person, possibly a woman who posed for Wikström in the fall of 1908.

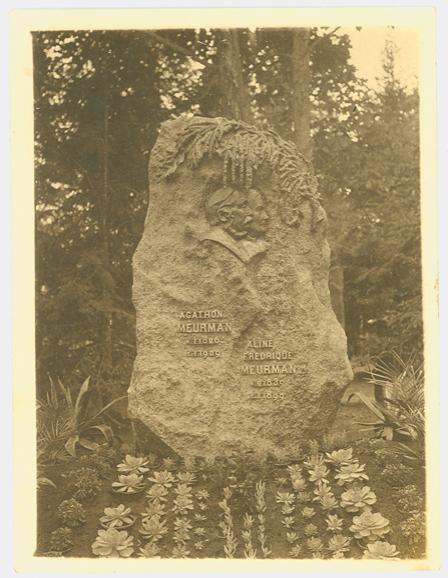

Kangasala – The Gravestone of Agathon and Aline Meurman

One of Wikström’s sculptures is also situated in the old cemetery of Kangasala. The sculpture in question is the gravestone of the notable Finnish conservative politician Agathon Meurman (1826–1909) and his wife Aline Meurman (1835–1899), unveiled in 1912.

The work was actually carried out following instructions from Agathon Meurman himself, and the stone comes from the Liuksiala estate owned by the Meurman family. According to a report of the unveiling, Wikström wanted to use natural stone to “highlight the modest character of the Meurmans’ and at the same time reflect the nature of the country to which they gave themselves wholeheartedly”.

Wikström had shared history with Agathon Meurman: Meurman was a central figure in advocating the building of Säätytalo (the House of Estates) in Helsinki in the late 1800s, and was also a member of the delegation responsible for its decorative frieze –Wikström had won the competition for its execution. Judging by the praising speech Meurman gave at the unveiling of the frieze, he was also more than pleased with the result. Possibly due to this success, Meurman was the subject of several of Wikström’s works, for example his portrait A. Meurmanin muotokuva, which was first exhibited in the autumn of 1900.

What makes the Meurman gravestone special for its era is that, at least according to contemporary commentator Eino-Sakari Yrjö-Koskinen, it was only the second memorial in Finland, “in which a woman’s contribution to the great patriotic work carried out by her husband was fully acknowledged”, and the first, “in which this acknowledgement was given to a spouse, a wife”.

This speciality actually seems peculiar in relation with Meurman’s reputation as an archconservative and an opponent of the women’s rights movement. According to historian Vesa Vares, however, Meurman’s critical views of the women’s rights movement did not stem from a lack of appreciation toward women, but a conception of different roles for men and women: women’s duties were at home with the family, whereas the affairs of the society were man’s responsibility. Meurman did praise his wife’s exemplary achievements in her own field, and for good reason, as Aline Meurman managed to take care of not only her nine children, but the notably large household of the Liuksiala manor, too. No wonder Agathon Meurman wanted to take her contribution into account in their gravestone. But, evidently, this appreciation was still not enough to put her in the foreground in the relief! Perhaps the crossing of some lines was still unthinkable.

K. G. Wikström – organ manufacturer

Kangasala is connected to Wikström’s life also by his older brother, Karl Gustav (1861–1908), who studied to become an organ manufacturer there. Already from a young age, Karl was known as handy and musical, and as a result of studies carried out all the way in America, too, he developed into a competent craftsman.

The organ of Visavuori, completed in 1905, was built by Karl in his workshop in Naantali, southwestern Finland. Originally Emil had wanted an organ in the first Visavuori, too, because he thought the instrument would have an invigorating effect on his art. According to Wikström’s daughter Mielikki Ivalo, the organ stopped working properly after it was moved into the new expansion of the atelier in 1912. This made Wikström, who previously had played the organ beautifully, change his instrument to the flute.

After Karl, the family tradition of organ manufacturing was continued by his son Erkki Valanki, who worked at the Kangasala organ factory from 1912 to 1970. The impressive brick-built building of the factory, which is situated near the old cemetery of Kangasala, has now been renovated into apartments.

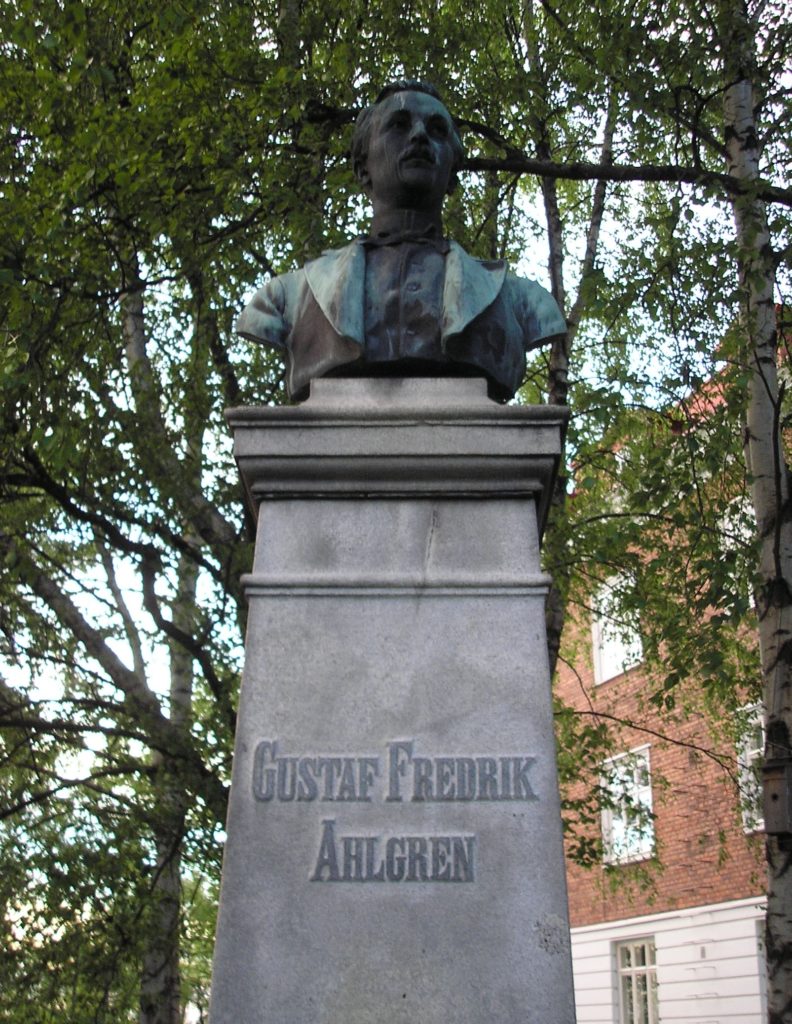

Tampere – Pohjan Neito -Fountain, the Bust of G. F. Ahlgren and the Gravestone of Jaakko Gummerus

The most significant of Wikström’s works located in Tampere is the Pohjan neito –fountain, which is situated in the north end of Hämeenpuisto-boulevard. Local businessman Nikolai Tirkkonen commissioned it as a gift to the city of Tampere in 1909. The fountain was drawn by architect Birger Federley following Wikström’s design, and it was unveiled in July 1913.

According to Mari Tossavainen, the fountain symbolizes Tampere and its character as an industrial city in various ways. The pools of water represent “the rapids, the strength and prosperity of the city”, whereas the Pohjan Neito, weaving a golden fabric as well as the statues on the lowest level, symbolize the city’s industry. Interestingly, Wikström used his own mother and daughter Anna-Liisa as models for one of the statue groups on the lowest level.

Professor and man of letters Eliel Aspelin-Haapkylä – he, too, a long-term acquaintance, supporter and, after his death, also the subject of a headstone by Wikström – reported in the newspaper Uusi Suometar of the fountain’s unveiling. He saw it as meritorious and wished to congratulate the artist for the “perfect success” of this “grand undertaking”. The citizens of Tampere seemingly agreed. According to Aspelin-Haapkylä, a worker present at the unveiling had addressed Wikström and said that the fountain was even a bit too much: “This is too beautiful for us, we haven’t deserved this!” The story is funny, because the people of Tampere are stereotypically seen to be humble to the degree of self-parody – apparently some things never change!

The Pohjan neito –fountain is not the only link between Wikström and Tirkkonen: some years later Wikström also carved the bust of Tirkkonen’s wife, Fanny Tirkkonen, which, according to Mielikki Ivalo is in the collections of Tampere Art Museum. In addition, there were more informal connections between the Wikström and Tirkkonen families. In her memoirs, Mielikki Ivalo recounts shopping in the Tirkkonen store, visiting their villa, and even an emerald pin given to her by Nikolai Tirkkonen.

There is also an early work by Wikström, the bust of the merchant Gustaf Fredrik Ahlgren (1888), located in Tampere. The sculpture is placed in the yard of the Koukkuniemi home for the elderly, which was originally built with funds donated by Ahlgren. Both the Pohjan neito -fountain and Ahlgren’s bust can be found with the help of The Statues of Tampere -database, brought to you by the Tampere Art Museum.

The third work by Wikström located in Tampere is the gravestone of bishop Jaakko Gummerus (1870–1933), which was unveiled in Kalevankangas cemetery in June 1936. The work on the gravestone dates to a phase in Wikström’s career, when he was already dethroned from his position as the leading sculptor of public monuments in Finland. During this phase, the emphasis of Wikström’s works shifted toward gravestones or grave memorials, which he made in the dozens during his later years.

Repetitive work on gravestones seems to have been perhaps a bit tiring for the artist. Yrjö Suomalainen tells how Wikström might come storming from his work and wave a model photograph complaining: “Look at this face! And I should make something out of it. But what can you do, when there’s absolutely nothing to work with”. Still, a sculptor had to make a living somehow: “Oh, the bread, the bread…”.

It is hard to say, whether Wikström felt inspired to do the gravestone of Gummerus, but some extra inspiration might have come from the fact that, as was so often the case, he had known his subject personally. The orderer of the work had thought that due to their personal connection, Wikström would know how to create a memorial that would be compatible with Gummerus’s humble character – that is: a work, which would be beautiful and dignified, but lacking any kind of pomposity. This approach sounds like something he was already familiar with from his work on the Meurmans’ gravestone!

The gravestone is not completely in its original state nowadays: it was damaged in the bombings during the Winter War, and a part of the stone had to be replaced and the relief had to be recast. One can use the online map of Kalevankangas cemetery to locate the gravestone, but it is not absolutely necessary: the headstone is situated right next to the chapel and therefore easy to find.

Vilppula Cemetery – Serlachius’ Relief and Jurvelius’ Gravestone

Vilppula and Mänttä, nowadays Mänttä-Vilppula, which functioned as the base of the Serlachius family, is another concentration of Wikström’s works. The local Serlachius Museums have a virtual service, which one can use to familiarize oneself with Wikström’s works in the area.

In the Vilppula cemetery there are two Wikström’s works side by side. The first one of these is a bronze relief of factory owner G. A. Serlachius and his wife Alice Serlachius (1913). There are actually interesting similarities between this work and the gravestone of Agathon and Aline Meurman: a natural stone is used as a base in both, and both reliefs also picture the profile of each of the spouses. This similarity is made apt by the fact that G. A. Serlachius and Agathon Meurman were old friends, who had for example collaborated in promoting the acquisition of the first Finnish icebreaker.

In the gravestone there are also the names of four of the Serlachius’ sons, who died as infants. At the bottom there is the name of Axel Ernst Serlachius, the only one of the family’s sons who reached adulthood. Axel Ernst also had a tragic life: at the beginning of the 1900s he was ousted from his place as his father’s successor as the leader of the Mänttä factories, in 1911 he went bankrupt, and finally ended his own life in 1922. Wikström carved a bust of Axel Ernst, as he did of G. A. and Gösta Serlachius, too.

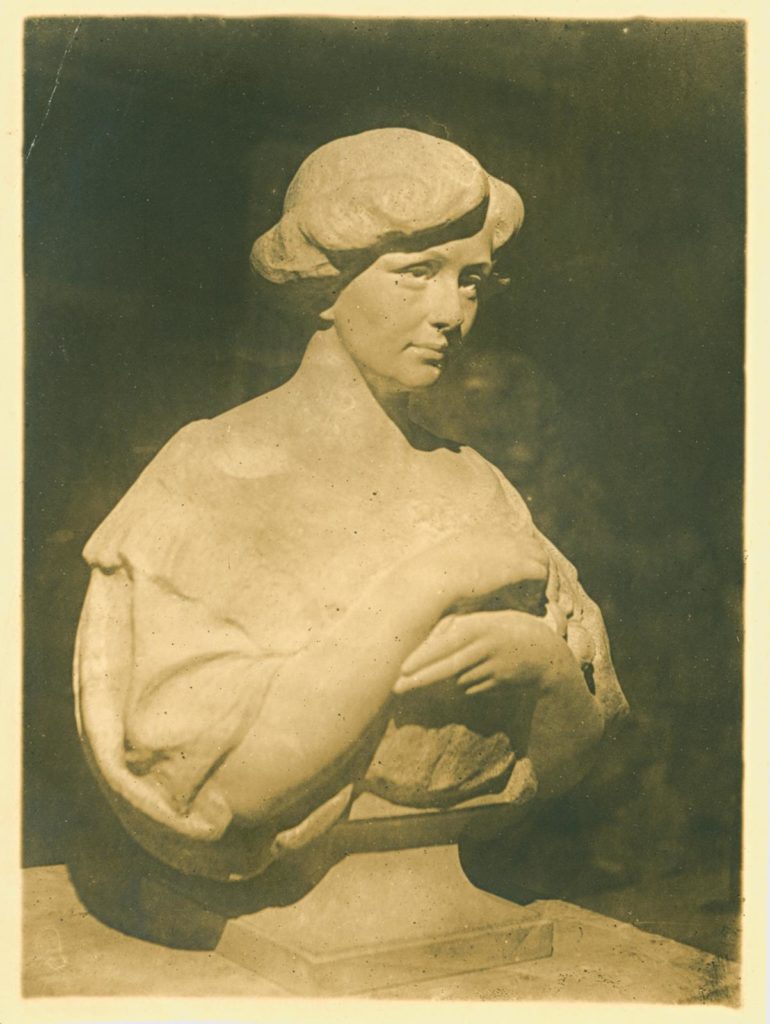

Located right next to the Serlachius’ gravestone is the hidden gem of Wikström’s works in the Pyhä-Näsi area: the beautiful, marble gravestone of Wladimir and Thyra Jurvelius. Thyra, the daughter of G. A. Serlachius, commissioned it as the headstone for his husband Wladimir, deceased in 1905, and it was unveiled in August 1907. In the top of the stone there is a portrait of Wladimir surrounded by a rose vine, and at the base there is a natural-sized figure of a grieving woman. On the other side of the stone Wikström designed an art nouveau -styled ornament.

The Jurvelius’ gravestone is presumably the largest sculpture in Finland made of white Carrara marble – the block of marble it was carved from weighed a formidable 9600 kilograms. The carving itself was quite a task: according to Mari Tossavainen, Wikström complained afterwards how hard it was to work on, and how it “ruined my whole summer”. Wikström’s assistant Aukusti Veuro was even hospitalized due to lung ailments caused by plaster and marble dust. There was trouble with the transportation of the work, too, as the roads to Vilppula were in bad shape due to heavy rain, but finally the sculpture reached its destination. Wikström eventually thought that it turned out a success, and even bemoaned the fact that it ended up so far in the countryside, out of the limelight of the capital, Helsinki.

Mänttä – The Serlachius Collections and Monuments

In Mänttä, less than ten ilometers from the Vilppula cemetery, the works of Wikström can be found in the collections of the Serlachius Museums – for example Gösta Serlachiuksen muotokuva (1920) and Akseli Gallen-Kallela suksilla (1906, cast 1941). In addition, in the park of the Museum Gösta, there are Wikström’s Kalapoika (Poika ja ahven, 1888, cast 1917) and Kuokkamies (1908).

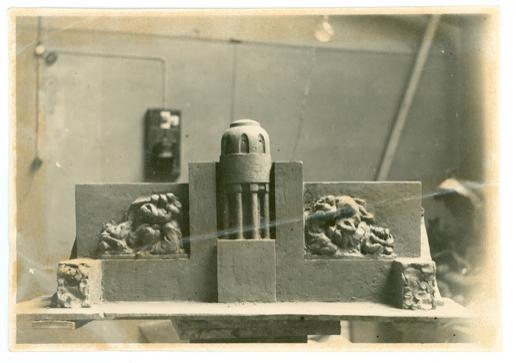

Wikström’s public works can also be found in the centre of Mänttä. Just in front of the Mänttä factory is located a sizable – over 21 meters wide and four meters high – memorial for G. A. Serlachius (1921). Its center point is the bust of Serlachius himself, flanked on both sides by granite reliefs representing male figures.

The work wasn’t originally meant to be as massive as it came to be: at first Wikström was only requested to make a new version of his bust of G. A. Serlachius for the 50th anniversary of the factory, but Wikström himself suggested a more sizable monument. His proposition was ready in 1916, but the work was delayed, and the monument was ultimately unveiled in 1921. It was moved to its present place from the other side of the street in 1957.

In Mänttä cemetery is also located the grave memorial of the Serlachius family, designed by Emil Wikström and W. G. Palmqvist. It is the largest of Wikström’s works of its kind, and its completion was a long and eventful process. Gösta Serlachius commissioned the memorial after the death of his youngest child in 1916, but the plans made then were not carried out due to the civil war of 1918, and perhaps also the fact that Mänttä did not yet have a cemetery.

The project was not abandoned, however, and it was restarted in 1928 at the inauguration of the Mänttä church, where Serlachius brought up the project once again. Wikström was pleased by this turn of events, as he had liked his idea and worked hard on it. Construction started in 1933, following plans simplified for financial reasons. W. G. Palmqvist, who had also taken part in the execution of the G. A. Serlachius memorial, designed the new version. Only the group sculptures on each side of the monument remained of Wikström’s original plans. The monument was completed four years later, in October 1937.

The Serlachius’ graves are situated behind the monument, on top of a mound, with a spiral staircase leading to them. The first person to be buried in the family grave was Gösta Serlachius himself, who died in 1942. Apparently, before that, a memorial stone of Gunvor, the daughter of Gösta Serlachius’ second wife Ruth, was situated there. The stone was made by Wikström in the 1920s.

LITERATURE AND SOURCES

Agathon Meurmanin ja hänen puolisonsa hautapatsaan paljastus. Uusi Suometar 26.6.1912, 5.

Forssan, Valkeakosken ja Varkauden museoiden tietokanta: http://www.piipunjuurella.fi/. Luettu 5.12.2018.

Ilvas, Juha: Kuvanveistäjä Emil Wikström. Teoksessa Emil Wikström. Herkkyyttä ja voimaa. Gösta Serlachiuksen taidemuseo 17.5. – 31.10.2002. Gösta Serlachiuksen Taidesäätiö 2002, 11–45.

Ilvas, Juha: Näyttelyteokset. Teoksessa Emil Wikström. Herkkyyttä ja voimaa. Gösta Serlachiuksen taidemuseo 17.5. – 31.10.2002. Gösta Serlachiuksen Taidesäätiö 2002, 56–129.

Ivalo, Mielikki: Emil Wikström tyttären silmin. Teoksessa Vuorinen, Olli (toim.): Visavuoren vaiheilta. Kustannusliike Kapitteli. 1969.

Ivalo, Mielikki: Visavuoren paljasjalka. Nuoruudenmuistoja ja päiväkirjoja vuosilta 1907–1927. (toim. Pirjo Tuominen). RKS Tietopalvelut Oy 2014.

Keskisarja, Teemu: Vihreän kullan kirous. G. A. Serlachiuksen elämä ja afäärit. Siltala, Helsinki 2010.

Kuuliala, Annamaija: Hohteessa menneiden kauniiden kesien. Taidetta ja taiteilijoita Sääksmäeltä. Sääksmäki-Seura 1992.

Liisa Lindgren: Memoria. Hautakuvanveisto ja muistojen kulttuuri. SKS Helsinki 2009.

Lindqvist, Leena ja Ojanen, Norman: Visavuori. Emil ja Alice Wikströmin koti ja ateljee. Teoksessa Lindqvist, Leena ja Ojanen, Norman: Taiteilijakoteja. Otava, Helsinki 2006, 133–151.

Julkiset veistokset. Valkeakosken kaupungin verkkosivut: http://www.valkeakoski.fi/portal/suomi/kulttuuri_ja_vapaa-aika/julkiset+veistokset/. Luettu 5.12.2018.

Pelto, Pentti: Suomen historiallisia urkuja. Rakentajat. Sibelius-Akatemia, Kirkkomusiikin osasto. Virtuaalikatedraali: http://www2.siba.fi/shu/rakentajat.html. Luettu 4.12.2018.

Pitkänen, Maritta: Serlachiukset ja Emil Wikström. Teoksessa Emil Wikström. Herkkyyttä ja voimaa. Gösta Serlachiuksen taidemuseo 17.5. – 31.10.2002. Gösta Serlachiuksen Taidesäätiö 2002, 46–55.

Pollari, Kaarina: Vilppulan kirkkomaa, sen muistomerkkejä ja ihmisiä niiden takaa. Teoksessa Kemppainen, Raimo (toim.): Vilppulan hautausmaa ja kirkot. Vilppulan seurakunta 1994, 49–112.

Silvennoinen, Oula: Paperisydän. Gösta Serlachiuksen elämä. Siltala, Helsinki 2012.

Suomalainen, Yrjö: Visavuoren mestari. Piirteitä Emil Wikströmistä ihmisenä ja taiteilijana. Otava Helsinki 1982.

Tirkkonen Marja-Liisa: Suomalaisia kulttuurikoteja. WSOY Porvoo-Helsinki-Juva 1997.

Tossavainen, Mari: Emil Wikström. Kuvien veistäjä. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Helsinki 2016.

Vainio, Matti: ”Nouskaa aatteet!”. Robert Kajanus. Elämä ja taide. WSOY, Helsinki 2002.

Vares, Vesa: Meurman, Agathon (1826 – 1909) kartanonomistaja, valtiopäiväedustaja. Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu: https://kansallisbiografia.fi/kansallisbiografia/henkilo/4569. Julkaistu 6.9.2001. Luettu 21.11.2018.

Vihavainen, Timo: Taantumusmiehen muistelmia. Vihavainen-blogi: http://timo-vihavainen.blogspot.com/2016/07/taantumusmiehen-muistelmia.html. Julkaistu 31.7.2016. Luettu 5.12.2018.

Virkkunen, Paavo: Agathon Meurman. Henkilö ja elämäntyö. III. 1881–1909. Otava, Helsinki 1957.

Vuorinen, Olli: Emil Wikström ja Visavuori. Teoksessa Vuorinen, Olli (toim.): Visavuoren vaiheilta. Kustannusliike Kapitteli 1969.

E.S. Yrjö-Koskinen: Meurman-puolisoiden hautapatsas Kangasalan hautuumaalla. Joulujuhla 1.12.1912, 11–12.