During its one and a half century of existence, Naapuri has been packed with a one-of-a-kind quantity of cultural history: elite culture, underground culture, and everything in between. The amount of material and objects within its walls is so vast that probably no one knows what it exactly contains – probably not even Iivu. It is thus a fascinating, unopened treasure chest – almost like a Ruovesi-version of an unlooted pharaoh’s tomb. So, let us sit back and relax and let Iivu take us on a journey into the hidden secrets of Naapuri and the history of his family!

The History of Asunta-atelier and Naapuri

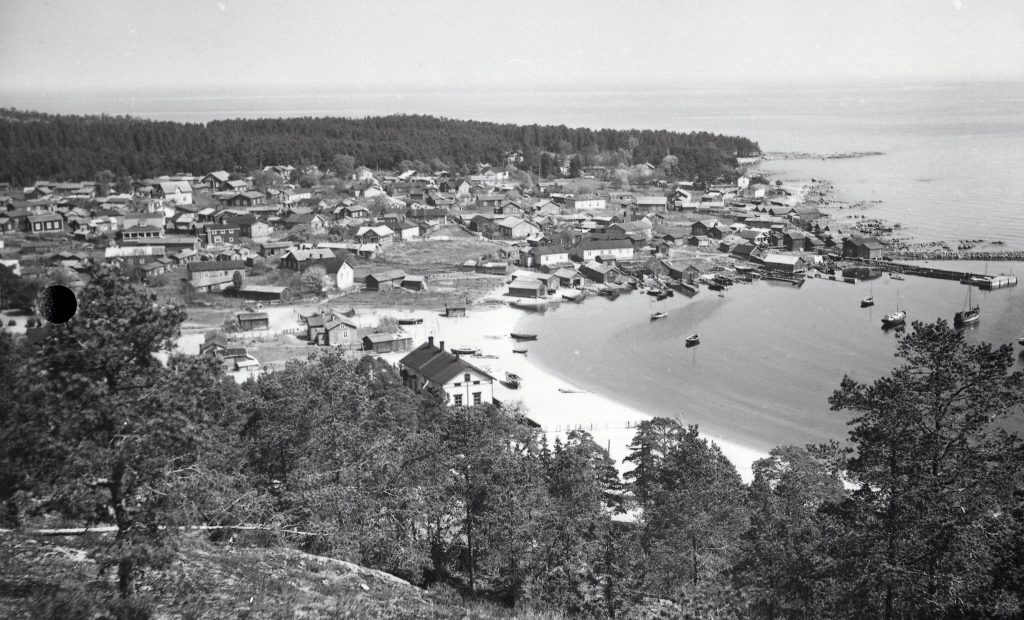

The shared history of the Asunta family and Naapuri began in 1936, when Iivu’s grandparents Heikki and Iris Asunta (originally de Bruyn-Ouboter) bought the house – Iivu heard from his grandmother Iris that they got it ”at a ridiculous price, as no one wanted such an old shack at the time”. Heikki and Iris renovated the house and also installed an attention-grabbing specialty for the time: ”a lot of people thought it was showing off when they built a toilet inside”.

According to Iivu, there is differing information of the year of Naapuri’s construction: 1852 and 1860. It may also be that neither one of them is right, and the house was actually built during those years – one must keep in mind that all the beams of the house were manually carved: ”in those days there were no prefabricated elements, which you can put in place with a machine, like, in a few days”, which meant that construction took its time. In any case the house has a history over a century long.

Originally the house was inhabited by cantor Peltonen, and judging by books found in its attic, it also housed Ruoveden Junttikoulu, a ”predecessor of a grammar school”, according to Iivu. There is also ”a Bible with the signature of Uno Cygnaeus on its front page”, which means that the so-called father of the Finnish grammar school system has possibly visited the house.

Iivu has lived his whole life in Naapuri, and could not imagine any other life for himself – life in a one-room flat in an apartment building would not suit his personality. This was foreseen by his grandmother Iris, who ”left a will, she knew that I am a person who respects […] and she knew that I could not live anywhere else but here”, and also ”that I won’t sell anything”. The will included a ”lifetime right of use and possession” of Naapuri for Iivu, which means that thanks for the preservation of the house in its current state go largely to Iivu’s grandmother and her foresight.

Nowadays the house has found another caretaker in Iivu’s cousin Harri, who ”agrees that we want to keep the house as it is”, and in 2015 a foundation, Heikki ja Iris Asunnan säätiö, was established to uphold the house and its cultural legacy. Despite the foundation, life in Naapuri is meagre, and there is little money for restorations. Fortunately Iivu tells ”he doesn’t need much to get by, so everything is OK” – ”I just try to keep the house in good condition and well, you can hear the crackles from the fireplace, I heat the house with wood and we try to manage without much money”.

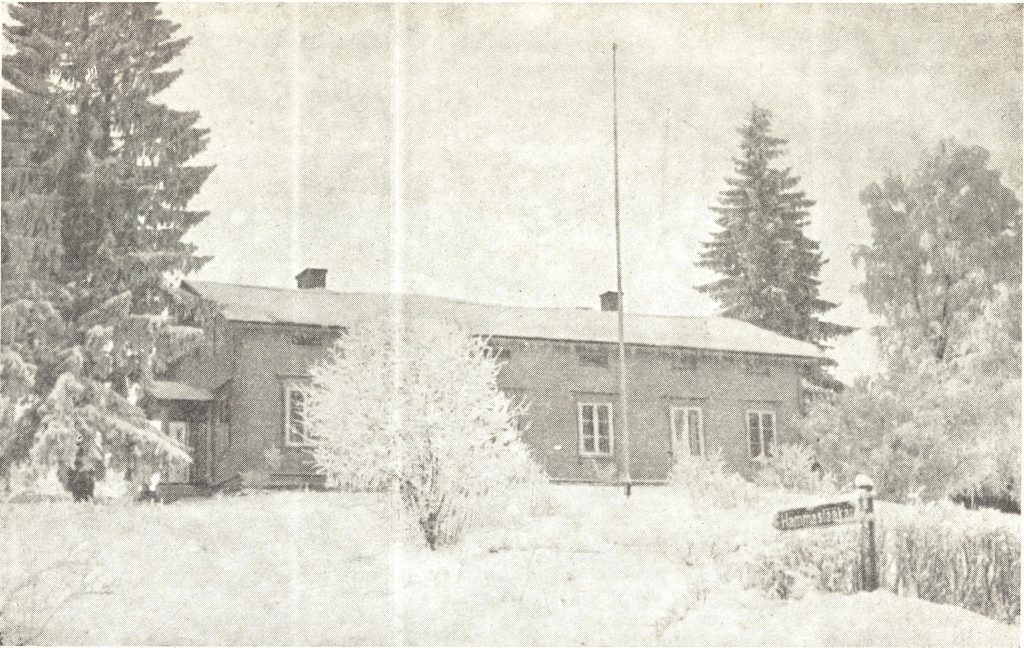

The public display window of Naapuri is the Asunta-atelier, which is open for a week in the summertime. The atelier has hosted several exhibitions connected to the Asunta family: Iivu mentions the exhibitions of Heikki and Iris Asunta, and Kiyoshi Ishii, who is a friend of Iivu’s aunts. There has also been a joint exhibition of Iivu’s aunt Kaijeli Asunta and Anneli Kuronen.

The atelier itself is, according to Iivu, ”a neighbour’s old drying barn” and was moved to its present place in 1948. To be precise, only the frame or body of the barn was moved, and the balcony and fireplace, as well as ”the interior and windows were designed by Heikki”. Iivu tells that before its new life as an atelier, the barn was used to accommodate the neighbour’s cows.

The atelier is not the only imported building in the Naapuri yard. Iivu tells that also ”the so-called little barn dates back to the middle of the 17th century and was moved here from Mäkipeska”, but Iivu cannot remember the exact year. Mäkipeska is the house of Aukusti Mäkipeska, a well-known statesman from Ruovesi, which is situated approximately twenty kilometers from Ruovesi to the direction of Virrat.

The barn thus has a long history, which is also marked by an honorary plaque of the foundation for peasant culture on its wall. And because we are talking about Naapuri, there is of course a behind-the-scenes story connected to the attachment of the plaque. According to Iivu, Anna Valtonen, who worked as a cattle maid next door in the house of Poukka, was helping out in Naapuri during the event. Later Anna told Iivu what an ordeal the attachment was to her: ”when they were nailing the plaque and she had made coffee and she was inside there when the gentlemen came and started singing and giving speeches and she had a terrible need to pee but she couldn’t get out”. One can therefore say that at least one person went through a major struggle for the honorary plaque!

There isn’t as exact knowledge of the history of all of the buildings. The mangle barn behind the atelier was, according to Iivu, brought there from someplace, but he has no conception of its original location or the time of its import. In addition, there is a building called the bicycle shed, the laundry room of the woodshed and a playhouse designed by Heikki Asunta, an outhouse, and a sauna. The designs of the sauna were drawn by Heikki on a cigarette pack, and have survived in Naapuri. The outhouse, in turn, ”was mainly for grandmother’s patients”, but ”it, too, was important for grandmother even though it is out of sight but […] because it was designed by Heikki”.

Grandfather Heikki

Despite his notable literary and artistic output, Iivu’s grandfather Heikki Asunta is nowadays a somewhat forgotten figure. After his time there have been few texts about him and, there is, for example, no published biography, even though he was quite a notable writer, and even received state prizes for literature in the first half of the 20th century.

Iivu thinks that the main reason behind Heikki Asunta’s present lack of fame are his political opinions – that is, his overt sympathy toward and connections with right-wing extremism and activism. In the book Suomalaiset fasistit (Finnish fascists) Heikki Asunta is even characterized as ”one of the fiercest and most outspoken white (right-wing) poets”. Asunta did, for example, work as the editor of the newspaper of the youth organisation of the right-wing movement IKL. For his literary services he even earned the nickname ”the court poet of the IKL” – which he himself saw as an honorary title.

An already deceased relative of Iivu has stated that ”Heikki Asunta should have been put on a pedestal but his opinions were […]”. Indeed: Asunta’s opinions were those of the losers of the Second World War and after the war they were to be put under the rug – or to be hidden in the attic. Iivu points at two framed drawings on the wall of Naapuri and tells: ”those posters there, or those sketches, I found in our attic sometime […] they were there on the bottom of a pile, as after the war they were really sensitive stuff”. Iivu’s mother’s husband took the posters to be framed in Tampere, and they were thus salvaged. As such Iivu thinks there is ”nothing bad” about the sketches: ”there’s only a Finnish flag on the background, but but but”. What makes the sketches aggravating is their intended use. According to Iivu, they are ”sketches for IKL posters”. Iivu remembers that he even has a letter somewhere ”from an IKL district office” asking to ”send those sketches this way”.

There is also other memorabilia from those ”blue and black” years of Heikki Asunta’s life within the walls of Naapuri – somewhere. Iivu recounts how, as he was younger, he found ”an awesome photo”, with ”geezers with suits on […] it’s like a school photograph […] there they are in two or three rows and on top there’s an inscription to brother Heikki, Heikki Asunta ’from us muiluttajat’” – muiluttajat used here as a nickname for extreme right-wing activists. According to Iivu, the picture was sent to Naapuri by Vihtori Kosola, the figurehead of Finnish right-wing extremism in the 1930s, with whom Asunta apparently had close relations with. Iivu tells that for example ”that Vihtori Kosola’s book […] its cover is drawn by Heikki Asunta”. The book Iivu refers to is Kosola’s autobiography or memoir Viimeistä piirtoa myöten, the compilation of which Asunta also participated in.

The interaction between the Asunta and Kosola families did not stop in the 1930s. According to Iivu, he too has visited Kosola: ”it was some time ago, but […] I was attending some festival in Lapua – I am acquainted with the offspring of Kosola – […] and […] somehow I ended up in the Kosola house”. The young master of the house – also named Vihtori – “happened to know that Heikki Asunta had visited them” and that he and Vihtori Kosola had been “good friends”. Therefore he welcomed Iivu: “God damn, Asunta is coming […] Asunta is coming to Kosola!”. By chance Iivu had more in common with the young Kosola than just shared history, as they both happened to have “Harley-Davidson tricycles”. Iivu has also heard that Vihtori had “gone around Ostrobothnia some time ago with a gavel intending to establish Vihtori Kosola MC, the most right-wing Harley-Davidson motorcycle club in Finland”. Iivu reckons, however, that “he probably did not get that many members”.

Iivu himself did not get to meet his grandfather, but even a stronger bond has been seen between the two – Heikki died about nine months before Iivu was born, and it has been joked that Iivu is his grandfather reborn: “we are said to be exactly similar in character and […] I am a little nicer”. Grandfather Heikki was, according to Iivu, also a nice man, but more hot-headed than his grandson. This is exemplified by a story Iivu heard from grandmother Iris, in which the writer Oiva Paloheimo had to vacate the Naapuri premises ASAP. The reason for his quick exit was that Heikki had appeared behind him with an axe. What exactly had caused Heikki to arm himself is unknown: “I don’t know if it was jealousy or what it was”. Paloheimo had, however, returned soon as he knew that “Heikki loses his temper quickly but he’s not angry for long”.

Iivu also has a story of another of Asunta’s writer comrades, the poet Lauri Viita, who, despite his contrary political sympathies, was good friends with Asunta. Iivu tells how “the brothers had sailed back and forth on the steamship Tarjanne for a few weeks and then Lauri Viita left for a so-called rest-home or actually a mental asylum to dry out. When he left the asylum he advised to send the bill to Heikki Asunta, because it was all his fault.” This proved to be, according to Iivu, the end of the men’s interaction with one another. Some evidence of their friendship remains, however, in Naapuri: “The owner of the antiquarian bookshop Komisario Palmu asked publicly some time ago if there would happen to be books by Lauri Viita with his signature in them, so I immediately showed him four or five such copies”. But, due to the strict collection policy of Naapuri, none of them were for sale.

Grandmother Iris’s Family and the People of Naapuri

One of the most precious treasures of Naapuri, and a piece of art in itself, is the photo album of Grandmother Iris’s family and friends. Iivu recounts how Jouko Rekola from the TV-show Rojua rojua examined the album pondering whether it was the product of a certain individual, when it would be “really valuable”. But in the end, it does not matter – the album is not for sale and therefore “its value in money is meaningless”. But this does not make it worthless in the eyes of Iivu, quite the opposite: “I’ve always thought that if, if this house would catch fire, that album would be the first thing I’d grab a hold of and rescue”.

Also the photographs inside the album, dating back even all the way to grandmother Iris’s grandparents, are treasures themselves. First in the album one comes across a photo of young grandmother Iris, or then just Iris, and Iivu accompanies it with a beautiful portrait hanging on the wall Naapuri, portraying her at the age of fifteen. Based on this evidence, Iivu states that “we are a beautiful family”, which is also corroborated by the fact that Iris’s niece Yvonne became Miss Finland in 1954 – she is still the only Miss Finland of noble background!

Grandmother Iris has clearly been an important figure in Iivu’s life, and was quite a character herself. Her original surname was de Bruyn-Ouboter, and even though she was born in Finland, she came from a Dutch family. Iris’s father was a German citizen and worked as a veterinarian in Suonenjoki and Sortavala. According to Iivu, Iris was born in Sortavala, but otherwise Iivu has no clear conception of “how things went”. When the family moved to Suonenjoki, they left behind a “really fancy mansion”, and also in Suonenjoki they had “a big house”, which they, however, lost, because “the father of the family was a German citizen and was not allowed to own in Finland”. Iivu actually is a bit puzzled by the fact that despite all this, grandmother did not bear a grudge against the Russians. He speculates that the reason might be that husband Heikki “as a man of the extreme right would have ranted enough already”. In any case, furniture brought from grandmother’s home remains in Naapuri, so “something is still left from there”.

After Iris graduated from high school she, according to Iivu, went to study medicine, and, following her father’s suggestion, specialized in dentistry. Iivu does not know exactly how she met her future husband Heikki Asunta, but it happened in Suursaari, an island on the Finnish Gulf, which belonged to Finland before the end of the Second World War. Iivu’s knowledge is complemented by Heikki Asunta’s niece Maija Asunta: according to her pro gradu thesis Iris visited Suursaari already in 1927 with her class and was infatuated “with the idyllic quality and the unspoilt nature of the place so that she definitely wanted to come back”. She returned two years later, in the summer of 1929, when Heikki was also on vacation on the island. By chance the two were accommodated in the same house, got acquainted, and that was it: the summer was spent together wandering on the rocks, listening to the roar of the waves on the beaches, and dancing in the casino. They spent the next summer together there, too, after which they started to see each other in Helsinki, the city where Iris studied.

Sounds romantic, and apparently that was the case – Heikki Asunta has later described that summer of 1929 as “the happiest of my summers”. It also seems that the feelings of Heikki and Iris did not fade later on, either. One gets such an impression from Maija Asunta’s thesis, according to which “Iris Asunta was an understanding and unselfish spouse, who managed to support and encourage his husband even in harder times”. On the other hand, Heikki Asunta “understood the exceptionally fine character of his partner and gave it his recognition”. The published recollections of Heikki Asunta also exude warmth and appreciation toward his wife.

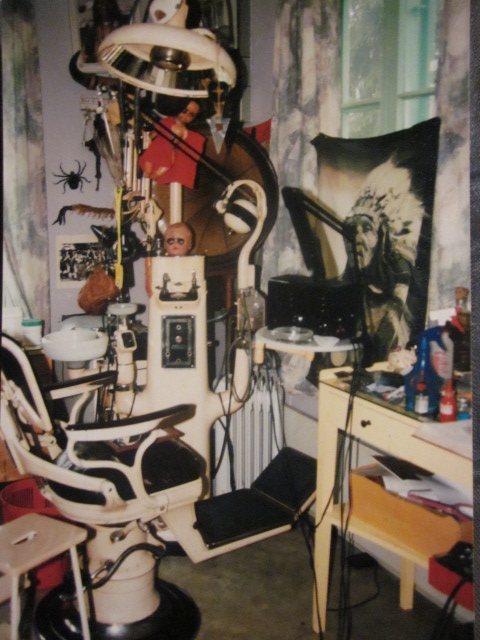

The romance of Heikki and Iris was a princess story reversed, on a par with the plots of Harlequin-novels: “they fell for each other there and then an offspring of a noble family moves here, to the middle of nowhere, all because of love”. In Ruovesi Iris started as a dentist’s practice, and as there were no other dentists nearby, she would tend to the local’s teeth “from morning to night and on weekends, too”. Her slightly terror-inducing dentist’s chair is still in Naapuri, and Iivu made use of it when he worked as a tattoo artist.

Next in the photo album one comes across grandmother Iris’s mother Signe Boman, her father Ernst de Bruyn-Ouboter and her sister Lola, who also, according to Iivu, lived “her last years” in Naapuri. Featured in the photos is also grandmother Iris’s little brother Junker, whose life ended at an early age in a tragic way. According to Iivu, he “shot himself as a protest”: “Junker had gone, did the Parliament House exist then already, well, he was an officer, so he gave his calling card to that Russian and shot himself, as he wanted to live in Finland and not in the Soviet Union”.

Iivu says that this happened some time in the 1930s, when Junker’s daughter Réa was still a small child. And truly, in the January 10th issue of Laatokka-newspaper from the year 1933 there is the obituary of Junker Ernst de Bruyn-Ouboter and a small news article, according to which he “died suddenly” in Helsinki on the 5th of the same month. More light on the event is shed by Käkisalmen Sanomat -newspaper from the same day, in which again a small news article ”Itsemurha eduskuntatalon portailla” (suicide on the steps of the Parliament House), tells how:

On Thursday afternoon at 4.30 p.m. mechanic Junker R. de Rruyn [sic] shot himself in the temple with a small handgun. Right next to him was a guard officer, who escorted B to the surgical hospital, where there was nothing else left to do but state that the shot had been fatal.

Counting from the birth date mentioned in his obituary, Junker seems to have taken his own life just a couple of weeks after his 24th birthday. Quite a thing to do – especially when one considers he had a small daughter. According to Iivu, Réa moved to Naapuri after the incident and “spent her childhood here with our grandmother”. Later on Réa became Réa Vainio, and she made herself a career as a flight attendant.

There are not only pictures of relatives in the album. Iivu shows some “wild pictures”, which feature German “grandmother’s father’s cadet comrades”. What makes the photos wild is the fact that several of the persons have “a cut in their cheek” as a mark of a duel. Iivu tells how “when they got the cut they had to go and take a photograph, it was a matter of honour to them”. It was all a part of a student tradition and there was also a special term for the mentioned “cut”, but Iivu doesn’t remember it right away. It does not come up searching the web either, at least not easily, but information about the phenomenon can be found: the tradition was called “mensur fencing” and was indeed a long-standing tradition in German student life.

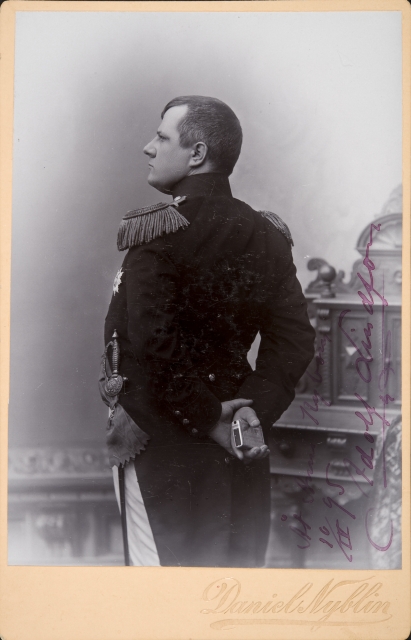

In addition to German duellists, the album also features a photo of another belligerent-looking person, dressed in a Napoleon-type uniform. The man in question is not, however, a general or an officer, but “the famous actor Adolf Lindfors”, who, according to Iivu, was “so infatuated” with Signe de Bruyn-Ouboter, the mother of grandmother Iris, that he had given her this “fan photo” with a dedication. Lindfors was no small player in the world of Finnish theatre at the time – in his peak years he was, in the words of historian Kalevi Kalemaa, “among the very top of Finnish theatre art” and, in the beginning of the 1900s, even worked as the director of the Finnish National Theatre. Lindfors would thus have been a quite a catch, but it seems that the infatuation never developed into a romance. Also, it seems that Signe was not the only one of Lindfors’s crushes that did not get beyond the starting line: according to some sources, Lindfors was also rejected by the most famous Finnish actress of her time, Ida Aalberg.

”For choppers, American cars and rock’n’roll!”

As mentioned, Iivu himself has dabbled in various fields of human culture – and often among the forerunners in Finland.

A significant part of his legend is the fact that he established the first tattoo studio in Finland. Iivu takes up the story: ”Somehow tattoos have always fascinated me and I’ve liked to draw ever since I was a child so […] my friends told me that since you can draw why not start tattooing”. Iivu himself got his first own tattoos in Denmark and from there it started: “Then I […] why the heck not, why couldn’t I, too”. Iivu asked the local rural police chief what it takes to start a studio, and as Iivu already had a suitable space in the house in the form of grandmother Iris’s former dentist’s room, all it took was ”a business registration and whatnot”. That’s how simple it was then, at least, around the middle of the eighties.

The work of a tattoo artist was so colourful that Iivu thinks that one could write ”a tattoo artist’s memoir” about it – ”yes there were such, such magnificent cases, and less magnificent, it was a peculiar business”. The tattoo studio had customers ”from all walks of life”: ”minors – with the permission of their parents, of course – then there were pensioners, policemen, and people on a vacation from prison, priests and […] men, women – nearing the end there started to be more women than men”. Geographically the customers came from the whole of Finland, and some even from abroad. The latter, according to Iivu, did not come to Finland ”specifically to be tattooed by me” – more likely the reason was that ”there were some pictures of my tattoos in U. S. magazines, international magazines, so some who were on a trip in Finland anyway just decided to get a souvenir”.

Iivu’s last years in the tattoo business were in first years of this millennium – he says that ”it must be fifteen years or more since I quit”, and nowadays he has ”done something small for a friend perhaps once a year, but not like officially”. The reason for quitting the business was that it became monotonous: ”people stopped asking for anything else than tribal tattoos”. Iivu wanted to be ”an artist of some sort” and when doing tribal tattoos he felt he ”couldn’t show what he could do”. He mentions a colleague once saying that ”doing a tribal tattoo is like painting a wall of a barn with a toothbrush, it’s like, that boring”.

A possible outlet for Iivu’s artistic ambitions might nowadays be an airbrush, but, ”we’ll see”. There would even be commissions ”if I only would to bother to take up the brush”, but inspiration is lacking. Also, now and then there would be demand for pictures for vehicles, but, according to Iivu, ”it’s so laborious, and I don’t really have a place to work in, as there’s absolutely no room for me to work here”.

Iivu’s adventures in the sphere of politics are also the stuff of legend. He actually ran for parliament ”a couple of times” and on the first attempt even managed to get ”a heck of a lot” of votes. On the second time around he wouldn’t have run anymore, but another dissident cultural figure and politician, Veltto Virtanen, ”talked him over”.

On the first attempt Iivu had a clear theme: ”there are so many of us of voting age or who are eligible to vote who are not in the least interested in politics that there should be a candidate for us, too”. The other of Iivu’s themes ”for choppers, American cars and rock’n’roll”, expressed the holy trinity of his lifestyle. There was even a personal election slogan, ”out with the old clowns, in with the new one”, which was later on used successfully by Tony Halme, a wrestler and actor who had a brief career in politics. For Iivu, however, the doors of the parliament remained shut, which may have actually been a blessing: ”Well, I just thought whether I would really go there, as I do not want to live in Helsinki”. Work as a member of parliament would indeed have meant an unwanted relocation and perhaps also a change in lifestyle. Perhaps it was all for the best!

Literature and sources

Literature:

Asunta, Heikki: “Rakas elämä, rikkain, suurin olet katveessa kuoleman”. Rislakki, Ensio (toim.): Me kerromme itsestämme. Kirjailijoiden yhteisjulkaisu. Otava, Helsinki 1946, 7–15.

Asunta, Maija: Heikki Asunta – ihminen ja kirjailija. Kirjallisuuden (kotimainen linja) julkaisematon pro gradu -tutkielma. Jyväskylän yliopisto, 1970.

History of Pori Jazz -www-sivut: http://historia.porijazz.fi/?classname=festivalyear&methodname=performer&lang=fi&artist_no=6139&year=1966&letter=e. Luettu 1.4.2019.

Hotelli Odessan kotisivut: http://www.hotel-odessa.com/en/history/. Luettu 23.4.2019.

Huhtamäki, Mikael: Live in Finland. Kansainvälistä keikkahistoriaa Suomessa 1955–1979. Gummerus, Helsinki 2013, 360–361.

Hyttinen, Tellervo: Heikki Asunta: taiteilijaelämää suurlakosta yöpakkasiin. Kotimaisen kirjallisuuden julkaisematon pro gradu -tutkielma. Helsingin yliopisto 1988.

Itsemurha eduskuntatalon portailla. Käkisalmen Sanomat 10.1.1933, 4.

Kalemaa, Kalevi: Lindfors, Adolf (1875 – 1929) näyttelijä, Kansallisteatterin johtaja. Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu: http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:sks-kbg-006212. Julkaistu 11.10.2005. Luettu 8.1.2019.

Kujanen, T. E.: Heikki Asuntaa tapaamassa. Ruoveden Joulu 1963, 28–29.

Kunnas, Tarmo: Fasismin lumous. Eurooppalainen älymystö Mussolinin ja Hitlerin politiikan tukijana. Atena, Jyväskylä 2013.

Kuolleita. Laatokka 10.1.1933, 2.

Luukkanen, Tarja-Liisa: Cygnaeus, Uno (1810 – 1888) kansakoulujen ylitarkastaja, Jyväskylän seminaarin johtaja, pappi. Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu: http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:sks-kbg-003176. Julkaistu 25.8.2000 (päivitetty 25.1.2012). Luettu 27.12.2018.

Rantanen, Seppo: Heikki ja Iris Asunnan Säätiö sr – Sata vuotta isänmaan historiaa. Esitelmä Suomalaisella Klubilla 1.12.2016.

Silvennoinen, Oula & Tikka, Marko & Roselius, Aapo: Suomalaiset fasistit. Mustan sarastuksen airuet. WSOY, Helsinki 2016.

Swanström, André: Hakaristin ritarit. Suomalaiset SS-miehet, politiikka, uskonto ja sotarikokset. Atena, Jyväskylä 2018.

Tyrkkö, Jukka: Suomalaisia suursodassa. SS-vapaaehtoisten vaiheita jääkäreiden jäljillä 1941–43. WSOY Porvoo-Helsinki, 1960.

Virtanen, Aarni: ”Toimikaa, älkää odottako”. Vihtori Kosolan puheiden muutokset 1929–1936. Jyväskylän yliopisto 2015. https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/47880/978-951-39-6396-5_vaitos16122015.pdf. Luettu 23.4.2019.

Wikipedia:

Kirjava “Puolue” – Elonkehän puolesta. https://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kirjava_%E2%80%9DPuolue%E2%80%9D_%E2%80%93_Elonkeh%C3%A4n_Puolesta. Luettu 23.4.2019.

Soittakaa Paranoid!. https://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soittakaa_Paranoid!. Luettu 23.4.2019.

Ravi Shankar. https://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ravi_Shankar

Luettu 23.4.2019.

Other sources:

Interview with Iivu Asunta on October 30th 2018.