The Thesleffs – Summer Residents of Murole

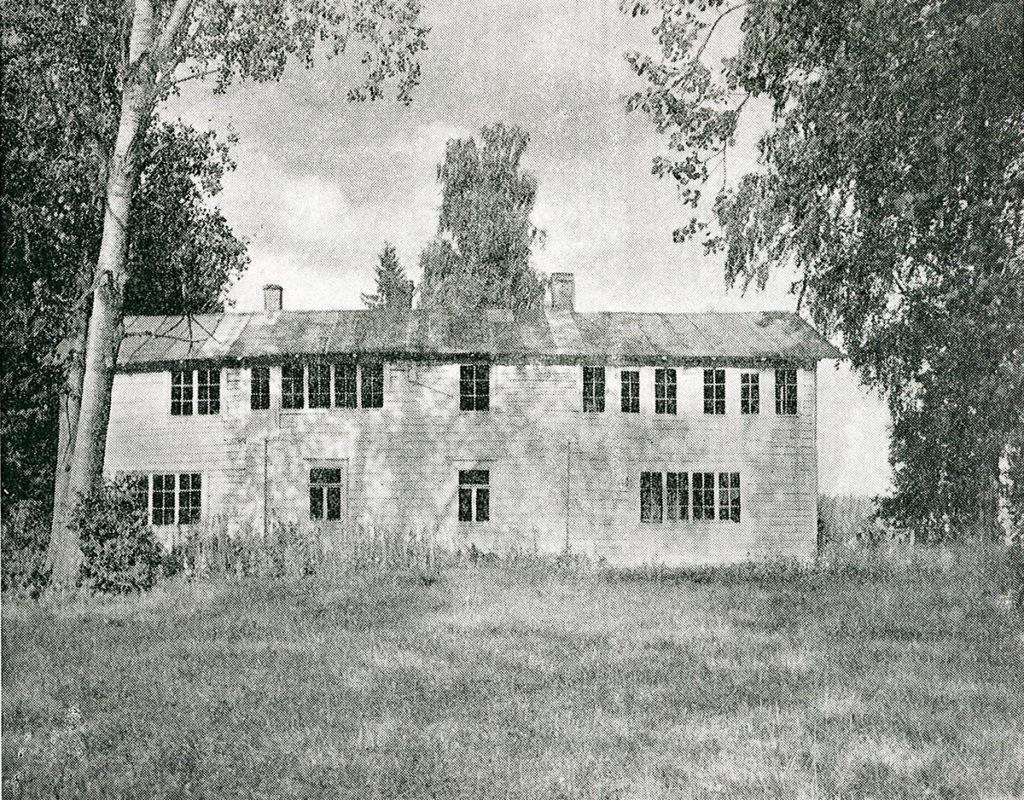

Ellen Thesleff’s family started to spend their summers in Ruovesi at the end of the 1880s, when Ellen herself was not yet twenty years old. Her father, Alexander Thesleff, fell in love with the scenery of the Murolekoski rapids and the abundance of fish in it, and in August 1891 the family bought Murolekoski estate as a permanent summer residence there.

The year in question was made significant also by to the fact that Ellen Thesleff made her breakthrough as an artist with her painting Kaiku (Echo), which she had painted in Murole. She made a name for herself and relocated to Paris to continue her studies, but returned to Murole again the next summer.

In August 1892 the Thesleff family was shocked by the death of Alexander Thesleff at the age of only 54. His passing, however, did not lead to the end of the family’s connection to Murole. The Murolekoski property was still retained, and Ellen continued to work there. During the years after Alexander’s death she painted for example Haapoja (1893) and Kevätyö (1894), which both depict the milieu of the Murole rapids.

Life in the ”White House”

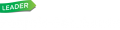

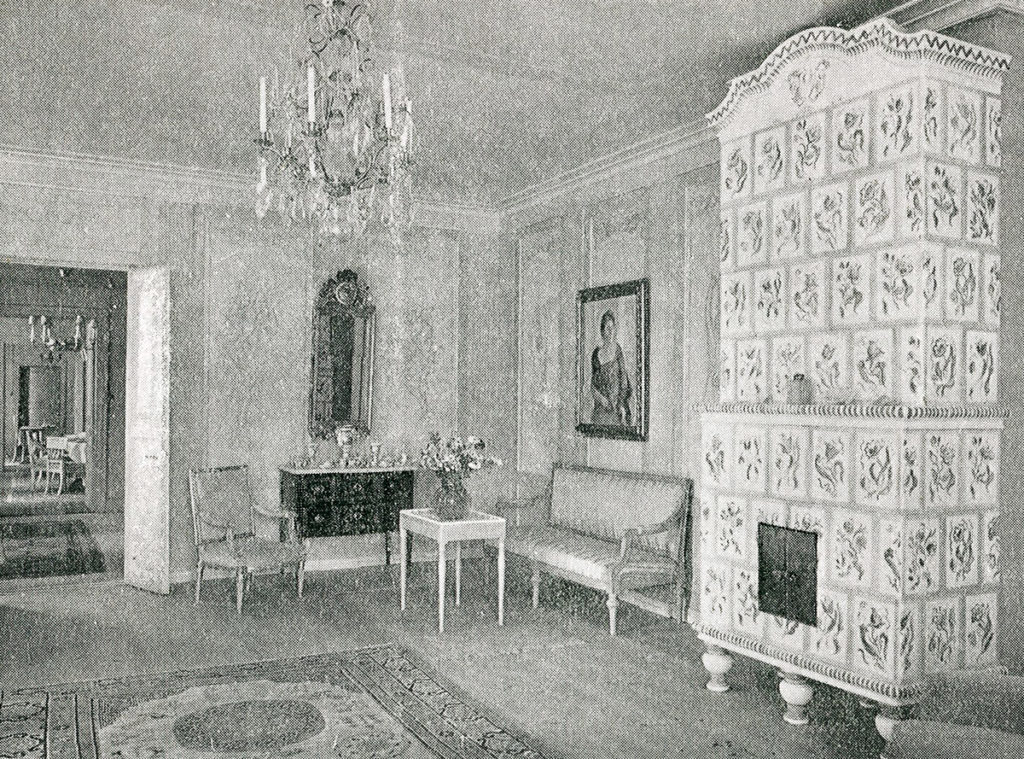

In 1898 the Thesleff family sold the Murolekoski estate, as its maintenance all the way from Helsinki proved too taxing. However, they still held on to some land on the other side of the rapids, where there was a small building used for accommodating travellers to Murolekoski. In 1899, following plans made by Ellen, it was expanded into a villa named Casa Bianca, ”the white house”.

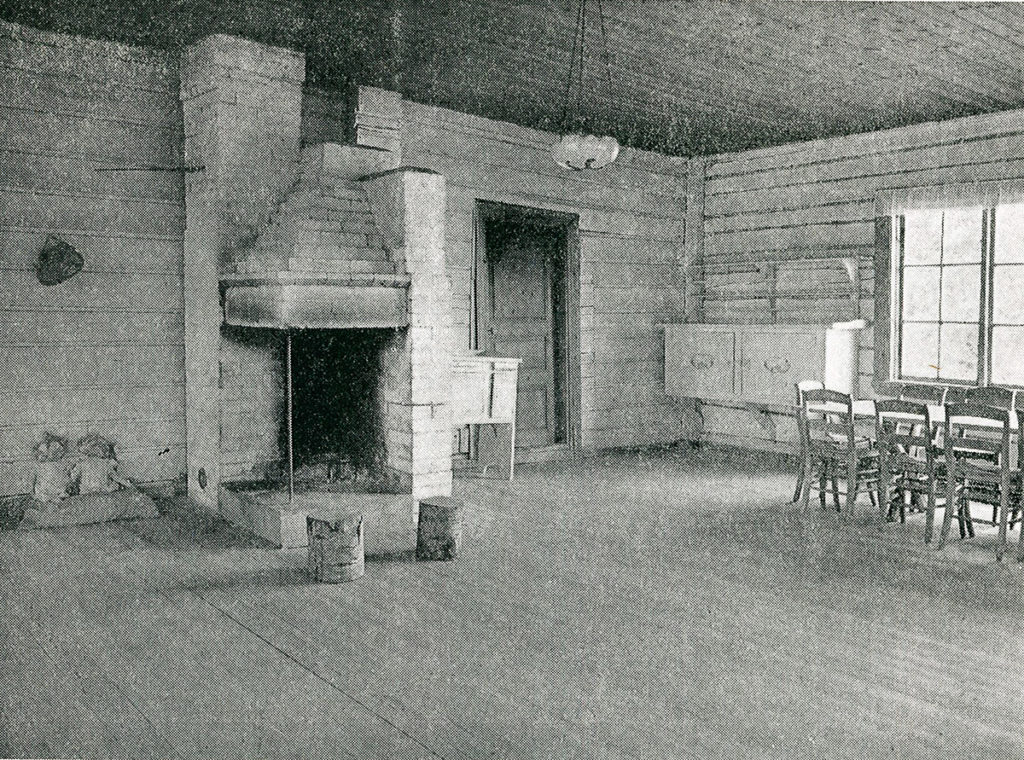

According to Thesleff’s biographer Hanna-Reetta Schreck, Ellen loved the new house right from the start and did not spare her troubles as she moulded it to correspond with her wishes. A lot of self-made furniture was built and Ellen decorated the furniture and rooms with ornaments. Also the house itself was modified quite freely: as the number of occupants rose, new rooms and sections were added, which created a special, patchwork-type of appearance for the house.

It seems that happy times filled with pleasant meals, self-organized masquerades, concerts, balls and plays were had in Casa Bianca. Apparently, the villa was at its liveliest during the first decades of the 1900s, when for example the Thesleff sisters, mother Lilli, uncles and aunts, the children of youngest sister Thyra, and the family of youngest brother Rolf might all be spending their summer there.

Ellen’s own private space in the villa was her upstairs studio, but she also painted in her ”living atelier”, the nearby Kissasaari (Cat island). The Thesleff family honoured and supported Ellen’s artistic aspirations by providing her with peace and quiet – she wasn’t obligated to participate in social life or housekeeping and was thus able to concentrate on her art. Also, the other members of the family were not allowed into her studio without her permission. These favourable circumstances proved productive: a great quantity of Ellen’s works are painted in Murole, often depicting its milieu, most of all the scenery of the Murole rapids.

Even though life in Casa Bianca was filled with culture and art, it was by no means luxurious. On the contrary, especially in the later years, when the house was inhabited mostly by Ellen and Gerda Thesleff, life was meagre: one story from those times even tells of beggars coming to the door of Casa Bianca but turning back after seeing the sisters’ thin and shabby appearance! According to local historian Kalervo Maunuksela also the sisters’ beds consisted of only straw mattresses on top of a few boards.

Another testament of material modesty is that a great amount of food eaten at Casa Bianca came from the surrounding nature. Fish was a mainstay in the diet, as it was easily available. In the 1920s Gerda Thesleff even supported the sisters by selling fish to ships passing by. Catching fish, as housekeeping in general, was Gerda’s task, but in the later years, when Ellen was left alone at the villa, she was a common sight on the Murolekoski bridge with her fishing rod.

On the other hand, the residents of Casa Bianca also enjoyed small luxuries now and then: for example, family tradition dictated that waffles had to be accompanied by wild strawberries – plain strawberries were not an option! Another luxury product was red wine, which Ellen Thesleff had grown to like in Italy. Ellen’s niece Margareta Thesleff-Sarvana has recounted how she even took a bottle of red wine with her as she went to visit Ellen Thesleff in the hospital shortly before Ellen’s death: “Of course it wasn’t suitable to bring wine to a hospital, and Ellen scolded me for it. But after we chatted for a while, she said contently: – You brought red wine, it’s good.”

Life in Casa Bianca may have also seemed a bit eccentric, at least to outside observers. Already in the 1890s, Ellen challenged conventional gender roles by cutting her hair short, and the sisters also dressed in outfits traditionally worn by men – Ellen’s preferred garb in Murole was an old grey corduroy suit and a cap. No wonder that Gerda and Ellen could be mistaken as men – or rather, due to their petite appearance, as boys. It was also unusual that when painting Ellen used an overall, in those times quite an unknown garment. Casa Bianca, too, was seen as even a bit spooky by the villagers – especially in the wintertime, when it was empty – and in the summertime it felt mysterious and fabulous.

The Murals of Pekkala Manor

The aura of mystery around the Thesleff sisters was not reduced by the fact that Ellen did not socialize much with the locals: interaction was limited mostly to the times when villagers brought berries to Casa Bianca or when Ellen used them as models. But there was a social side to living in the countryside, too. Especially Ellen’s relationship with the mistress of nearby Pekkala manor, Sophie von Kraemer, was warm.

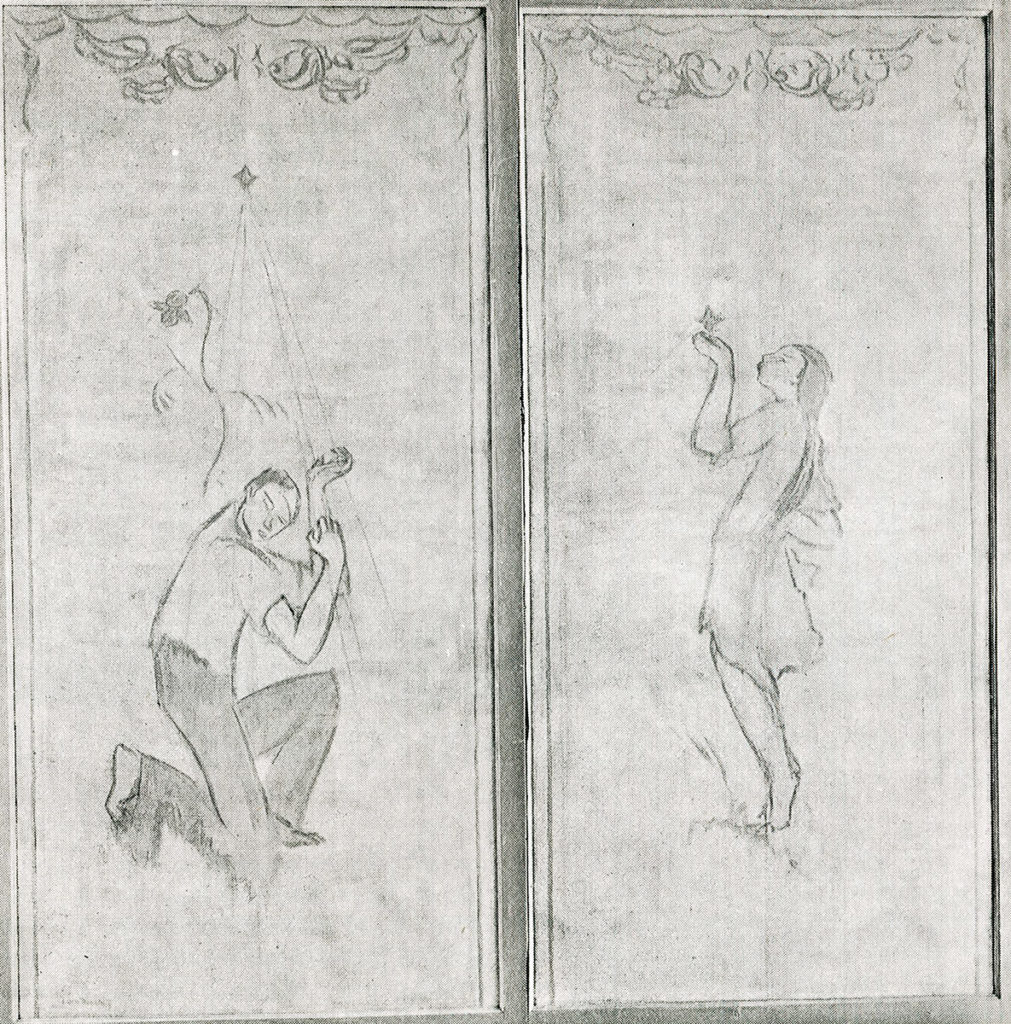

The close relations with the Pekkala household also led to a concrete manifestation. In 1928 Hans Aminoff, the master of Pekkala, commissioned Ellen to paint murals for the new part of the mansion, which was built the year before. The commission also included making plans for the decoration of a tile stove and some smaller surfaces.

For Ellen, the commission was a pleasant one, and that spring and summer she painted in Murole, visiting Pekkala from time to time to test the suitability of her designs. She used the four times of the day as the starting point of her pastel-coloured works. The names of the main subjects were Aamu (Morning), Päivä (Day), Ilta, (Evening) and Yö (Night). To represent these, Thesleff painted different human characters: two angels with trombones were the symbols of morning, day was represented by a young man with a scythe on his shoulder, the symbol of evening was a girl holding flowers in her hand and a man with the sun on his shoulder, and night was symbolized by a young male character playing with the rays of a star and a girl blowing on a star on her palm. Ellen also designed a grand carpet for the new hall, but its colours did not go well together with the other interior decoration, and so it was placed in the library upstairs.

After the murals were finished, Ellen and Gerda Thesleff left for Florence. It seems that any time money allowed, Italy, so important and inspiring for Ellen, was the sisters’ chosen destination.

The Altarpiece of Murole Church

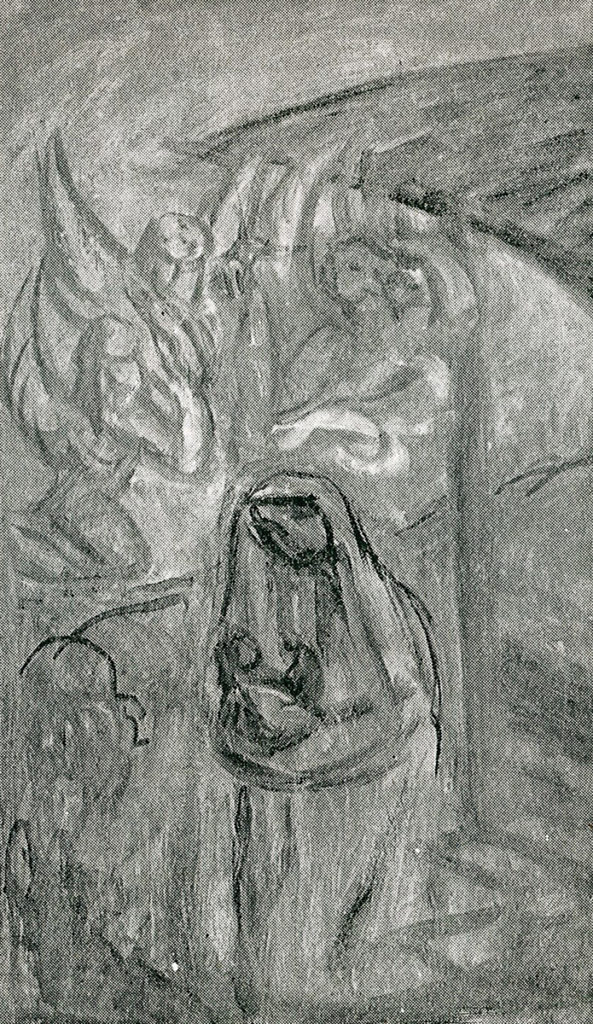

For a brief moment in the 1930s, it was possible that a painting by Ellen Thesleff would have adorned a notable public space in Murole. A new village church was being built, and a competition over the execution of its altarpiece was organized. Ellen Thesleff, too, took part in the competition with two works, the subject of both being the birth of Jesus. According to art historian Lars Pettersson, the works depicted Maria holding Jesus in her lap, kneeled before the stable at Bethlehem.

Thesleff-biographer Hanna-Reetta Schreck speculates that the religious theme and the church building perhaps did not inspire Thesleff the same way that the work at Pekkala manor did. The result was dark in its hues, and, to use Schreck’s phrase, ”possibly too hard to swallow” for the board selecting the altarpiece: it has even been suggested that the reviewers examined Thesleff’s work the wrong way around – that is, that they would have looked only at the backside of the work, which Thesleff had used to dry her paintbrush.

The story is funny, though a bit malicious – and who knows, it may be true, too! However, some doubts do arise by looking at one of Thesleff’s suggestions (pictured below). It may be, to quote Pettersson, ”more of a misty fantasy than a concrete subject”, but it is not by far abstract enough that one would err to examine its backside – unless Thesleff’s way of drying her brushes was highly artistic, or unless one would want to do so deliberately! This may, of course, be the case, and such an interpretation is presented by Kati Tervo in her Thesleff-novel Iltalaulaja (Night singer, 2017).

The final truth in this matter is, of course, hard to reach. The only thing certain is that Thesleff’s paintings, or any other works entered in the competition, were not accepted, and Murole church had to wait for an altarpiece for almost twenty years. The present altarpiece, Jeesus Getsemanessa (Jesus in Gethsemane) by Lennart Segerstråle, is from the year 1951.

Later on, the altarpiece debacle had an epilogue. It has been told that Ellen Thesleff was so disappointed with the outcome of the events, that she left her paintings at the church. According to Margareta Thesleff-Sarvana, they were “forgotten in a storage room between a cupboard and a wall, and no one seemed to know who they belonged to”. She offered to buy the works, and they certainly were not overpriced: her daughter Nina Sarvana tells that a water heater to warm up the water used for christenings in wintertime was deemed a suitable compensation. This way the works ended up once again in the hands of the Thesleff family, but there was yet one twist in their gloomy story: one of the paintings was destroyed in a fire in 1994.

The Altarpiece of Murole Church

Life in Casa Bianca gradually slowed down: in 1915 Ellen’s little brother Rolf bought the nearby Tokonen estate as a summer residence, and when mother Lilli died in 1919, Casa Bianca was inhabited mostly by Ellen and Gerda. After Gerda’s death in 1939, Ellen spent her summers in Murole alone – her last summer there possibly being 1949. Ellen’s permanent residence then was the Lallukka Artists’ Home in Helsinki, where she lived until her death in 1954.

When describing Casa Bianca in the book Taidemaalareita Ruovedellä (Painters in Ruovesi, 1955), Lars Pettersson provides a unique snapshot of a moment when only approximately a year had passed from Ellen Thesleff’s death – a moment, when the artist’s presence was still almost perceptible. Pettersson writes how the interiors of the villa were “more or less untouched”: the Egyptian-styled cupboard in Ellen’s studio was still in its place, as was the fishing rod in the stairs. Also, at their place on the mattress by the fireplace, were the dolls Adelaide and Ginevra, named after two old ladies in Forte dei Marmi, one of Ellen’s favored places in Italy. Also the photographs in Pettersson’s article, many of them published here, give the impression of a house the artist had only just left, perhaps to visit someplace, only temporarily gone.

In the 1960s Casa Bianca was demolished due to its terrible condition. The erstwhile state of the villa is reflected in Nina Sarvana’s recollection of Ellen’s niece, Isotta Söderhjelm. Isotta was spending her summer in Casa Bianca and was leaving back to Helsinki the next day, but decided to summon a local construction foreman to determine what should be done to the villa. After taking a glance at the building, the foreman said briefly: – You are a brave woman. I’d leave today, if I were you.

The villa and its interiors did not, however, vanish altogether. For example, the Egyptian-styled cupboard from Ellen Thesleff’s studio, as well as a grandfather clock, chairs and an old table with carvings of three huge fish caught from the Murole rapids, are still in the possession of the Thesleff family. Casa Bianca has also been immortalized in several photographs and Ellen Thesleff’s paintings, which can be used to imagine what their happy life in Murole was like.

An Ellen Thesleff Exploration

An excellent way to start an Ellen Thesleff -themed exploration is to do as Ellen would have done – that is, board the steamship Tarjanne at Mustalahti harbour and let it take you to the main destination of the trip, the Murole canal. You can make good use of the three-hour trip by just letting your eyes take in the beautiful lake scenery and your mind wonder. Another option, of course, is to read this article so you will be well prepared when you reach the destination! You can also have some lunch at the restaurant aboard, so that hunger will not hamper your exploration when you reach your destination.

While in Murole, the first benchmark of the trip is the Ellen Thesleff memorial, situated next to the canal. Erected in 2008, the memorial stone reminds of her longstanding life and work in the area and includes a motto she herself formulated for her art in the 1910s: ”Ei teorioita, ei muotoa, vain väri” (No theories, no form, just color). The restaurants at the canal are also a good place to take measures against hunger, in case you did not happen to have lunch aboard s/s Tarjanne.

If you move a few hundred meters east from the memorial, you find the bridge over the Murole rapids. There, if you glance to the north, you can see the view familiar from several Thesleff’s paintings. To the east you can see the buildings of the Murolekoski estate, where the Thesleff family lived in the 1890s, whereas situated to the west is the former site of Casa Bianca. However, it is important to remember that both are in private ownership and not open to the public. But not to worry, one can get in to Thesleff atmosphere from the bridge, too. If you look north from its west end, you can even see Kissasaari, the island that was both the birthplace and the subject of some of Ellen’s paintings. While walking across the bridge, one can also engage in a little historical re-enactment: this is the same bridge that the Thesleffs used to walk over, perhaps with fishing rods in their hands.

When leaving the Murolekoski bridge one can pay a visit to Murole church, the site of the unfortunate altar piece debacle: just follow the road east from the canal for approximately five kilometers, then turn left at the T-shaped crossroads and then, after a few hundred meters, turn left again and follow that road a few hundred meters more until you reach the church. If you wish to return to Tampere from Murole, we suggest you take the picturesque Rantatie route that follows the east bank of the lake Näsijärvi: First to Kapee, then Terälahti, then Maisansalo and Kämmenniemi and so forth. Enjoy!

Literature and sources

Literature:

Hoppu, Tuomas: Kulttuurihenkilöt Muroleessa. Teoksessa Hoppu, Tuomas (toim.): Kotiseutumme Murole. Ruovesiläisen kylän ja sen asukkaiden vaiheita eränkäynnin ajoilta nykypäivään. Muroleen Kylät ry, 2005, 354– 375.

Hälikkä, Siina: Ellen Thesleff – the secret of a long life. Teoksessa Ellen Thesleff: Värien tanssi. 5.6. –31.8.2008. Taidekeskus Retretti, 2008, 220–237.

Konttinen, Riitta: Täältä tullaan! Naistaiteilijat modernin murroksessa. Siltala, 2017.

Maunuksela, Kalervo: Casa Biancaa ei ole enää mutta muistot elävät yhä. Ruoveden joulu 1969, 12–15.

Pettersson, Lars: Ellen Thesleff. Piirteitä oleskelusta ja työskentelystä Ruovedellä. Teoksessa Taidemaalareita Ruovedellä. Louis Sparre, Hugo Simberg, Ellen Thesleff, Gabriel Engberg. Ruoveden muistojulkaisusarja II. Ruoveden Sanomalehti O.Y. Ruovesi 1955, 29–43.

Schreck, Hanna-Reetta: Ellen Thesleff – värien tanssi. Teoksessa Ellen Thesleff: Värien tanssi. 5.6. –31.8.2008. Taidekeskus Retretti, 2008, 8–81.

Schreck, Hanna-Reetta: Tanssi ja liike Ellen Thesleffin taiteessa. Teoksessa Ellen Thesleff: Värien tanssi. 5.6. –31.8.2008. Taidekeskus Retretti, 2008, 82–95.

Schreck, Hanna-Reetta: Minä maalaan kuin jumala. Ellen Thesleffin elämä ja taide. Teos, Helsinki 2017.

Suhonen, Martti: Muroleen kanava. Näsijärven helmi. Alueen historia, kulttuuri, merkitys ja tulevaisuus. Ruoveden Sanomalehti Oy, 1985.

Tervo, Kati: Iltalaulaja. Otava, Helsinki 2017.

Vilén, Reijo: Ellen Thesleff vietti Ruovedellä lähes kuusikymmentä kesää. Ruoveden Joulu 1998, 6–10.

Other sources:

Discussions between the author and Nina Sarvana July 17th and August 21st 2018.