Sääksmäki and the Slöör Family

Chronologically Gallen-Kallela’s earliest connection to the Pyhä-Näsi area was Sääksmäki, which he – then still named Axel Gallén – visited for the first time with his brother Uno in 1882. Gallén stayed in the Rapola manor as the guest of the family of Kaarlo and Aina Slöör, who he had gotten acquainted with during his school years in the 1870s. At first Axel befriended the sons of the family, Arthur, Rafael, and Mikael, but in time he became closest with daughter Mary Helena (1868–1947), who he eventually came to marry.

Gallén visited Rapola the next summer (1883), too, but his third visit four years later (1887) turned out to be the most significant one for his future life – and Mary’s, too. They had started a correspondence while Axel was spending the winter of 1886–1887 in Keuruu (see below), and even though Axel had planned to travel straight to Paris to continue his studies there, he stopped by at Rapola for a week. It was then that the love between Mary and Axel truly blossomed.

Sääksmäki thus came to have special importance in the lives of Mary and Axel Gallén. After the week of romance in Rapola, Axel returned to Paris, but Mary still spent her summers there, and the separation of the young couple was at times painful. The next time the couple met was late in 1889. It was then – on Mary’s birthday, November 20th, to be precise – that their life together could truly begin. Mary reached the age of twenty-one, which meant that she was now legally an adult. Thus her father, who had had doubts about their relationship, could not stand in the way of their marriage anymore. Axel and Mary were married in May 1890, by which time father Slöör had given his blessing to their union, too.

Starting their independent life as a married couple did not mean that Mary and Axel left Sääksmäki behind. Their firstborn, Impi Marjatta, was baptized there in September 1891, and the family was there also during Christmas time. Sääksmäki was the Galléns’ chosen destination also in late 1892, when they decided to move to the countryside from Helsinki, and also a year later, in late 1893, though on both occasions Axel stayed behind in Helsinki.

In the beginning of 1894 Axel left Helsinki and arrived in Rapola. This proved to be an intensive period during which he painted several of his most famous works, such as Ad Astra and Symposion. Gallén also had plans of building his atelier home in Sääksmäki. He looked for a suitable location with Emil Wikström, but it was hard to find. It is told that he had his eye on a place called Jylhänkärki, but after hearing the sound of a cowbell there, he decided that it was too close to settlement.

When the summer of 1894 approached, anxiety over unfinished works, the location of his atelier, and also the arrangements of their accommodation for the summer – the other members of the Slöör family also wanted to come to Rapola – took over the Galléns. In May Axel went searching for a lot in Ruovesi and found the land there more expensive than in Sääksmäki, which raised his doubts about whether ”fate would, after all, drive us to Sääksmäki”. A suitable place for the atelier was, after all, found in Ruovesi, where the Galléns moved in the fall of 1894. This did not, however, mean a total severance of ties to Sääksmäki. After 1894 Gallén visited Visavuori, the atelier home of Emil Wikström, several times, and also used subjects from Sääksmäki in his later works.

The Summers of Visuvesi

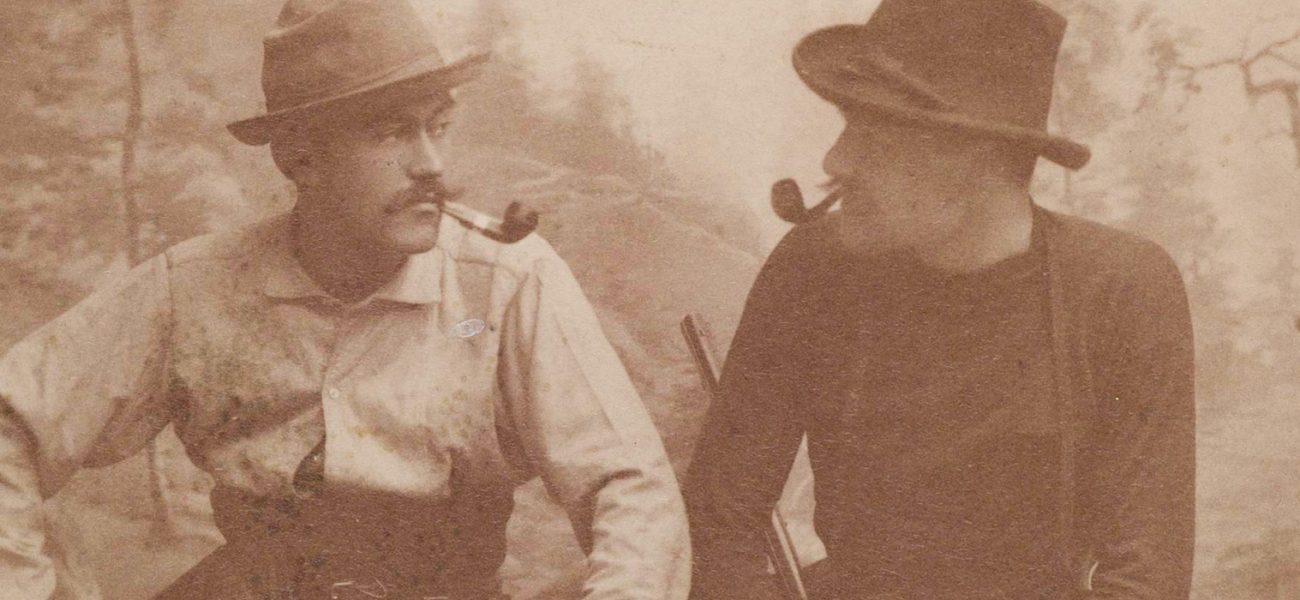

Gallén spent time in Visuvesi during two separate summers. His first visit was in June 1889, when he stayed long enough to paint Haavakuume, a work he saw as one of his best. Around mid-summer Gallén and his traveling companion, the Swedish artist Louis Sparre, traveled further to Keuruu and the croft of Ekola.

In the spring of 1891 Gallén once again felt the call of the wild, and headed to Visuvesi with Sparre. Summer camp was put up in Murtosaari, about twenty kilometers north from Ruovesi church, where they found an abandoned croft to live in. Gallén, Sparre, along with the sculptor Emil Wikström, settled into the island in the middle of July, and at the end of the month they were joined by Mary, the Galléns’ daughter Impi Marjatta, and maid Hilda. Gallén and his family stayed in Murtosaari until the beginning of September.

Gallén used the picturesque shores and small bays of the Murtosaari area as models for landscape paintings and his famous Aino-triptych. He was enamoured with the region and its populace, as well as the Helvetinjärvi-lake, where he took a trip with Sparre before Mary’s arrival.

The Summers of Keuruu – and a Winter

The area of Keuruu had a special place in the heart and art of young Axel Gallén. Aivi Gallen-Kallela has counted that in the 1880s Gallén spent a total of fourteen months there. During that time he painted circa one hundred works.

On his first, month-long visit to Keuruu in August 1884 Gallén painted for example landscapes and peasant architecture. He returned in January 1887 and stayed for nine months, painting some of his best-known early works. Only in September did he return to Paris to continue his studies.

For the third time Gallén headed for Keuruu in the summer of 1889, after finishing his studies in Paris. As already mentioned, he travelled with Louis Sparre, stopping first at Visuvesi. Around mid-summer, Gallén and Sparre moved to the Ekola croft in Keuruu, where Gallén continued his work. The summer of 1889 proved very productive for him: according to Janne Gallen-Kallela-Sirén, Gallén painted “over twenty notable works, including about a half a dozen masterpieces”. Aivi Gallen-Kallela has calculated that Gallén painted almost forty works during the cold and rainy summer – even though Gallén himself thought he really wasn’t even “on a roll”. Works Gallén produced include for example Tyttö Keuruun kirkossa and Saunassa. Also, Gallén and Sparre participated in organizing the later famous summer festivities in Keuruu in August, alongside other rising figures of the Finnish cultural life such as Arvid Järnefelt and Jean Sibelius.

The stay of Gallén and Sparre in Ekola ended with a sour note. Money was stolen from Sparre, and the thief turned out to be one of Ekola’s own people, a 25-year-old called Sakari, who, in his own words, had done it “for the honour of the people”. The incident was possibly linked to Gallén’s use of the maid of the croft as a nude model for his Saunassa-painting, which was unheard of. Contributing to leaving Ekola was also a dubious stomach bug, which both Gallén and Sparre caught. At least Gösta Serlachius (see below) has stated in his memoirs that the people of Ekola croft had actually tried to poison the artists by putting rat poison in their food. Gallén had a hard time accepting this breach, as he had lived in the croft for a long time and used its surroundings and people in several of his paintings. The unfortunate episode also caused an artistic setback: the painting Saunassa, which was supposed to be the magnum opus of Gallén’s Keuruu period, was left unfinished. This was a cause of great frustration for Gallén, who dubbed the painting harshly as a “worthless sketch”.

Contributing factors to leaving Ekola were also the longing Axel felt for Mary, and his yearning to venture farther into the wilderness, even all the way to Lapland. In a letter to Mary he stated being “fed up with all these peasants and other people I interact with, they seem to me so simple, bourgeois, and ordinary”. It seems that even the people of Ekola did not live up to the idealized image of the Finnish people he had created for himself.

Gallén and Sparre moved from Ekola to the old rectory of Keuruu to work on some unfinished paintings. In the beginning of October Gallén travelled to Helsinki to see Mary, but soon came back to Keuruu to continue his work. The return to Helsinki and Mary happened in the beginning of November.

When Gallen-Kallela made his fourth and last painting trip to Keuruu, the atmosphere had changed. In September 1917 he travelled first to Mänttä to meet Gösta Serlachius, then the head of the Mänttä factories, and they travelled together to the Ekola grounds. But the place was not the same anymore: the Ekola croft had been taken down, its residents were gone, and the woods surrounding lake Jamajärvi had been cut down. This was a shock, and made Gallen-Kallela reminisce melancholically about his past there.

According to Janne Gallen-Kallela-Sirén, ”for Gallén, Jamajärvi and its surroundings became a paradise in the countryside, which made a decisive impact on the development his art in 1880s and the decades to come”. The works painted in and/or inspired by the area have also had an impact on the Finnish self-image. Gallen-Kallela-Sirén points out that the landscapes and people of Gallén’s early works are nowadays seen as “artistic manifestations of ‘true Finnishness’”. Thus, these local landscapes of the region northeast from the lake Näsijärvi have become something of a “national landscape” of Finland.

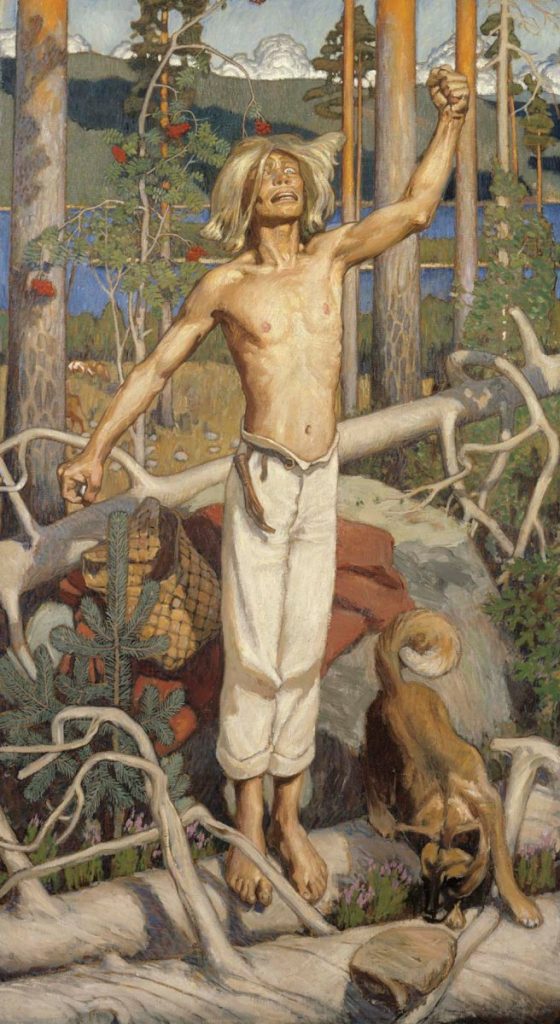

In 1917, the area that Gallén had painted in the 1880s, had changed totally. Still, even today, over a century later, something still remains: the rock that made its most famous appearance in Gallén’s painting Kullervon kirous (1897–1899), still stands at its place a few hundred meters north from Ekolanniemi.

The Maecenases of Mänttä

The peace and quiet of the Ekola croft was not the only thing drawing Gallén to the Keuruu area. Nearby Mänttä was the base of G. A. Serlachius (1830–1901), a friend and a sponsor of Gallén. According to Finnish art historian Maritta Pitkänen, the relationship between Gallén and Serlachius may have even been ”the most important relationship between an artist and a patron in our country”.

The artist and the ”Maecenas” met each other for the first time in Turku in 1884 and then again two years later in Paris, where it was agreed that Gallén would come to Mänttä as a guest. Gallén did spend the Christmas of 1886 there, and was feasted in the most lavish manner: ”I ate and drank for three days and two nights and returned to my croft in the woods a broken man, or even worse”, he confided in a letter.

In March 1887 Gallén was in Mänttä once again, possibly negotiating with Serlachius over his portrait, a painting he worked on during the same summer in Mänttä. The finished portrait did not please the Serlachius family, but after the painting had won the state prize, their critique abated.

The next time Gallén spent time in Mänttä was in 1889, while living in the Ekola croft. Then he painted the portrait of Sissi Serlachius, the 11-year-old daughter of G. A. Serlachius. He also painted the portrait of Sissi’s mother, Alice Serlachius, and possibly did sketches of decorations for the dining hall of the family. In the 1890s Gallén painted another portrait of Alice, which was yet again criticized by the family, and was deemed unsatisfactory by the artist himself, too.

Serlachius had given financial support to Gallén before, but in the beginning of 1889, it became regular: Serlachius started a monthly payment of one hundred marks to Gallén. He also sponsored the building of Gallén’s atelier, Kalela, by guaranteeing a loan for the building expenses, and also by providing extra funding when it was needed.

After the death of G. A. Serlachius in 1901, Gallén’s connection with Mänttä continued through his relationship with Axel, the son of G. A. Serlachius, and Gösta, his nephew. It is not known when Gösta Serlachius and Gallén were first acquainted, but according to correspondence, they knew each other at least from 1902. Altogether there is little information about their connections, but the most intensive phase of their interaction seems to have coincided with the first years of Gallen-Kallela’s second term in Kalela (see below). By 1919 Gösta Serlachius had acquired a total of 24 works by Gallen-Kallela.

Later on, the area of Jamajärvi, where the Ekola croft was located, became a connecting factor between the two men. Ekola had been owned by the Mänttä factories since 1907, even though the buildings that had been there during Gallen-Kallela’s time, had already been torn down. Tales of Gallen-Kallela’s sojourn in the croft awakened Serlachius’s interest in the place, and when in the fall of 1927 a lot there was offered for purchase, he bought it and changed its name to Huhkojärvi. Then he created the Huhkojärvi farm by joining some other crofts he had bought and some extra land to the area. In June 1930 an inauguration of a sauna was organized there, which became a get-together of old friends attended by Gallen-Kallela, Serlachius, and Emil Wikström, among others. The last time Gallen-Kallela visited the Serlachiuses was in November 1930, circa three months before he died.

The friend- and sponsorship between Gallen-Kallela and G. A. and Gösta Serlachius laid the foundation for the notable collection of Gallen-Kallela’s works in possession of the Serlachius Art Foundation. In total, the foundation has 180 of Gallen-Kallela’s works, which one can enjoy by visiting the Serlachius Museums of Mänttä.

Kalela – the Home and Studio in the Wilderness

As already mentioned, during the 1890s, Gallén felt a great need for a home and a studio in the wilderness, but had difficulties in finding a suitable location for it. Finally, Gallén found a place to his liking in Ruovesi, and negotiations for the purchase of the land were finalized in September 1894.

The construction of the atelier was begun in October, but the work did not proceed in the desired pace, and, also, the budget for the work proved to be insufficient. Feeling frustrated, Gallén left for Germany at the end of the year, leaving Mary and their four-year-old daughter Impi Marjatta behind in Ruovesi. This decision proved unfortunate, as while he was away, Impi Marjatta died of diphtheria. Gallén returned swiftly to Finland, but soon left again for England with Mary to take their minds off the tragedy.

Axel and Mary returned to Ruovesi in mid-summer 1895, but even then, the new home and studio was not finished. That summer was spent finishing the construction project, and it was only in the fall when the Galléns were able to move into their new house and Axel could concentrate on his art – at least partially. In addition to the grief caused by Impi Marjatta’s death, Kalela caused troubles of its own: the building was devoid of any conveniences, water had to be carried from a hole in the ice, wood had to be chopped for a total of ten fireplaces, and help was hard to find. Due to an error in planning, the workspace did not have one warm corner in it, just draft from wall to wall. In addition, Gallén was seriously in debt due to the unexpected scale of the construction project. And amidst all of this, the Galléns’ daughter Kirsti was born in August 1896.

Nonetheless, Gallén was very productive: in late 1895 he made, for example, his first woodcut Kalman kukka and stained-glass works, and also painted his nearby surroundings, local people and family. Gallén’s most notable and well-known artistic achievement during these first years in Kalela was a series of Kalevala-paintings, such as Sammon puolustus (1896), Lemminkäisen äiti (1897), and Velisurmaaja (1897).

From January to June 1898 the Galléns were in Italy, and after their return Gallén experimented with al fresco -painting, which he had familiarized himself with in Italy, and also made enhancements to the living and working conditions of Kalela. In addition, the children of Mary and Axel – Kirsti and Jorma, born in November 1898 – were christened in Kalela, with conductor Robert Kajanus and composer Jean Sibelius as godfathers.

During the latter half of 1899 Gallén was engaged in planning the interior decoration and frescoes of the Finnish pavilion of the Paris World Fair. The pavilion was completed in early 1900 and Gallén’s four frescoes received a lot of attention and appreciation. Sadly, the pavilion and therefore also Gallén’s frescoes were torn down the next year.

After toiling nine months with the frescoes, Axel and Mary returned home in May 1900. His next major project was the Kullervon sotaanlähtö –fresco for the music hall of the Student house in Helsinki, which he painted – with Mary as his assistant – in early 1901. When the fresco was unveiled in March, the Galléns were already back in Kalela, where Axel was planning his next work, the frescoes of the Jusélius mausoleum in Pori. He finished the sketches in early September, and before the end of the month, began painting the frescoes with Mary once again as his assistant. The work was finished in less than a month, but Gallén was not satisfied with the result. He was also a bit bitter, as he had realized he had sold his work to Jusélius for too modest a price.

In November 1901, for practical reasons, Gallén settled in Tampere. He worked on the Jusélius-frescoes in the building located at the corner of Kauppakatu and Aleksis Kiven katu, just beside the central square. Moving to Tampere ended his first period of living in Kalela, which had lasted for six years.

In the first half of 1902 Gallén did designs for the wilderness atelier of his sponsor Otto Donner, but his main focus was still on planning the frescoes. In April 1902 he was able to continue his work in Pori. While Gallén laboured with the frescoes, his family lived in Kuuminainen, situated 17 kilometers west from Pori, from where Gallén rode a bicycle to his work site every day.

In the fall of 1902 the Galléns settled in Pori. During the winter Axel completed the final sketches of the main frescoes of the mausoleum, which were then painted in the spring and summer of 1903. After the job was finished, Gallén returned to Kalela, but did not stay for long – it seems that the familiar wilderness landscapes did not inspire him anymore.

In December Gallén went on a long trip all the way to Spain, and did not return until May 1904. Back in Finland he did not have the energy to go back to Kalela, which was in need of considerable maintenance. He returned in September to pack some things, and then went on to the family’s temporary home in Kerava. In June 1905 the Galléns returned to Ruovesi, where Axel started to paint for example his new, grand Kalevala-inspired work, Sammon ryöstö, which he completed later in the year in Helsinki. After the summer the Galléns moved to Helsinki, and did not return to Kalela for a decade.

The Return to Kalela

Gallen-Kallela and his family moved back to Kalela in August 1915. It was the need for the peace of the wilderness, but also the fact that his other atelier home Tarvaspää in Espoo was in the middle of war preparations and had also been vandalized, that functioned as incentives for the return to Ruovesi.

If life in the wilderness atelier had never been free of difficulties, now things were even harder. During Gallen-Kallelas’ absence, forest had taken over Kalela, and as winter began, so began the immense chore of heating the house. Modifications on the great fireplace of the house were made by a local bricklayer to make heating easier.

After his return to Kalela, Gallen-Kallela painted landscapes, did etchings and was also immersed in making sketches for decorations for the entrance hall of the National Theatre. The latter work progressed swiftly: sketches for all of the nine paintings were finished early in 1916. However, the next summer Gallen-Kallela sold the sketches to commercial counsellor Tirkkonen (see also the text “The Sculptures of Emil Wikström in the Pyhä-Näsi Area”), which possibly reflected his commitment to the task. Actually, the job was never finished by Gallen-Kallela, but by Juho Rissanen in the late 1920s. A cause for the abandonment of the work may have been that Gallen-Kallela had finally managed to pay off his debts, and was no longer forced to take on assignments for the sake of money.

In late January 1918 civil war broke out in Finland, and Gallen-Kallela joined the White forces. He participated in the battles of Vilppula, but was soon appointed to Seinäjoki, where he, among other tasks, designed medals and decorations for the White army. Mary, on the other hand, spent the whole wartime in Kalela.

Gallen-Kallela came back to Kalela in July 1918, but did not stay long: in March 1919 he was summoned to the capital to work as an adjutant for the regent C. G. E. Mannerheim. After this duty ended in the summer of 1919, Gallen-Kallela returned to Kalela only to find that life there had become even harder than before. Help was increasingly hard to get, as many of the locals had fought on the enemy side in the war. But still, Gallen-Kallela managed to get some work done, too: for example landscapes, portraits and the painting Lemminkäinen tulisella virralla.

In the late summer of 1921 Gallen-Kallela had finally had enough of the difficult circumstances of Kalela and let his family know that a move was to be expected. In September the family’s belongings were loaded into two small steamships, and the life of the Gallen-Kallelas resumed in Porvoo, Southern Finland. Kalela was left empty for fifteen years, until Gallen-Kallela’s son, Jorma, and his family moved there in the summer of 1937.

LITERATURE AND SOURCES

Literature

Dahlberg, Julia & Mickwitz, Joachim: Havet, handeln och nationen. Släkten Donner i Finland 1690–1945. Skrifter utgivna av Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland 790. Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2014.

Gallen-Kallela, Aivi: Kalela. Akseli Gallen-Kallelan Erämaa-ateljee ja koti, Ruovesi. Teoksessa Lindqvist, Leena ja Ojanen, Norman: Taiteilijakoteja. Otava, Helsinki 2006, 173–221.

Gallen-Kallela, Aivi: Kaukokaipuu. Ruoveden joulu 1981, 5–7.

Gallen-Kallela, Aivi: Koko elämäni on siveltimessäni! Akseli Gallen-Kallelan neljä matkaa Keuruulle. Eripainos teoksesta KARHUNSOUTAJA. Keurusselän seuran 50-vuotisjuhlajulkaisu 1993.

Gallen-Kallela-Sirén, Janne: Minä palaan jalanjäljilleni. Akseli Gallen-Kallelan elämä ja taide. Otava, Helsinki 2001.

Holm, Tea: Spiritualismin muotoutuminen Suomessa. Aatehistoriallinen tutkimus. Helsingin yliopisto, Helsinki 2016.

Huusko, Timo: Viittatie jäällä. Teoksessa Leena Ahtola-Moorhouse ym. (toim.): Luonnon lumo. Pohjoismaalainen maisemamaalaus 1840-1910. Statens Museum for Kunst, Kööpenhamina 2006, 253.

Kuuliala, Annamaija: Hohteessa menneiden kauniiden kesien. Taidetta ja taiteilijoita Sääksmäeltä. Sääksmäki-Seura, [s. l.], 1992.

Kämäräinen, Eija: Akseli Gallen-Kallela – Katsoin outoja unia. Teoksessa Suomalainen Taidegalleria. WSOY Porvoo–Helsinki–Juva 1999.

Lahelma, Maria: Akseli Gallen-Kallela – Ateneumin taiteilijat. Ateneumin taidemuseo / Kansallisgalleria, Helsinki 2018.

Lindqvist, Leena ja Ojanen, Norman: Visavuori. Emil ja Alice Wikströmin koti ja ateljee. Teoksessa Lindqvist, Leena ja Ojanen, Norman: Taiteilijakoteja. Otava, Helsinki 2006, 133–151.

Luutonen, Ahto: Aikaisempien aikojen muistoa Ruovedeltä. Muistoja Akseli Gallen-Kallelan ja Louis Sparren Visuveden ajoilta. Ruoveden Sanomalehti Oy, Ruovesi 1973, 93–96.

Maunuksela, Kalervo: Aino-taulun maisemat. Ruoveden joulu 1985, 18–19.

Merisalo, Lauri: ”Pääskyn linna”. Ruoveden joulu 1975, Ruovesi 1975, 19–21.

Mäkelä-Alitalo, Anneli: Slöör, Kaarlo. Kansallisbiografia-verkkojulkaisu. Studia Biographica 4. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1997- (Julkaistu 23.3.2007, viitattu 24.7.2017). URN:NBN:fi-fe20051410.

Okkonen, Onni: A. Gallen-Kallela. Elämä ja taide. WSOY, Porvoo-Helsinki 1949.

Pitkänen, Maritta: Kultaisen polun kulkijat. Akseli Gallen-Kallelan, G. A. Serlachiuksen ja Göstä Serlachiuksen yhteisiä vaiheita. Gösta Serlachiuksen taidesäätiön julkaisuja 2008.

Palmén, Aili: Louis Sparre. Ensi kosketus Suomen erämaihin. Teoksessa Taidemaalareita Ruovedellä. Louis Sparre, Hugo Simberg, Ellen Thesleff, Gabriel Engberg. Ruoveden muistojulkaisusarja II. Ruoveden Sanomalehti, Ruovesi 1955, 7–14.

Simpanen, Marjo-Riitta: Kuvataiteilijoiden Keski-Suomi. Teoksessa Marketta Mäkinen (toim.): Maailmannavan elämää : Keski-Suomen merkitys suomenkielisen kansallisen kulttuurin ja taiteen muotoutumisessa vuosina 1880-1917. SKS, Helsinki 1994, 73–122.

Wikström, Emil: Muutamia muistelmia. Teoksessa A. Gallen-Kallelan muisto. Kalevala-seuran vuosikirja 12. WSOY, Porvoo 1932, 63–75.

Other sources

http://blog.kansanperinne.net/2011/03/gallen-kallelan-21-syntymapaiva-ja.html.

http://www.serlachius.fi/fi/kokoelmat/kuukauden-helmet/24-gallen-kallelan-omakuva/

Sähköpostikeskustelu Erkki Järvisen kanssa 23.–25.1.2019.