Both Taneli Santala (1784–1848), dubbed “the great witch of Ruovesi”, who operated in Murole, and Matti Mutila (1780–1864), also known as ”the god of Ruovesi”, were famous practitioners of their trade, whose services were sought from great distances. The reputation of Santala is, for example, reflected in the fact that he was depicted in Antero Warelius’s play Vekkulit ja kekkulit from the year 1848, even though by then named Matti Santala. Mutila, on the other hand, who was deemed an even more skilled conjurer than Santala, was regarded as ”our king” by the other sages of his time.

Despite their famousness in their era, nowadays both Santala and Mutila are quite unknown characters. As with Heikki and Hetastiina Hurstinen, there is apparently quite little recorded information about them – or, at least, it is not easily available. Some fascinating and even a bit chilling stories may still be found by going through local histories and newspapers. The following is a handpicked selection of these tales, exclusively for the travellers of Pyhä-Näsi!

Taneli Santala

Taneli Santala was born as the youngest child of the family in the house of Lammi, Kuru, in 1784. Once he married in 1805 he settled in Jouttijärvi, from where he moved to Murole with his family in 1829.

Santala was apparently a revered, but also feared character, which is expressed by several horror-story-like anecdotes of him. It is claimed, for example, that he signed a deal with the devil with his own blood, and thus swore himself to the devil’s service. There are also at least two versions of a story, in which a person coming to ask Santala for advice eavesdropped on his conversation with the devil.

In the version of this story that has made its way to the book Kotiseutumme Murole, Santala’s visitor asked for help to find his horse, and listened behind a wall, when the devil disclosed the whereabouts of the horse to Santala – and also revealed that they were listened to. This made Santala angry, and he threatened to break the eavesdropper’s neck. The devil, however, knew this to be impossible, as the visitor was behind three strong locks after having blessed himself in the name of the Holy Trinity. According to the story, the visitor was quick to leave, and eventually found his horse in the place disclosed by the devil.

Santala seems to have been a man of various skills in the field of witchcraft. Like the Hurstinen couple, he has been said to be capable of being in contact with the deceased. Also, it is told that he could stop forest fires only by showing up at the scene of the fire. Santala did not have to be afraid of thieves, either: he could leave his things unguarded anywhere and they were not stolen – and if somebody tried, they would freeze on the spot, unable to move.

And so it happened that after the wedding the provost’s finger started aching badly, and could not be remedied with the means of conventional doctors – the provost even travelled all the way to Tampere to seek help. The provost’s wife then decided to take the matter in her own hands, and sent a farm hand to meet the witch with a jug of liquor. The farm hand asked for a remedy right away, but the witch took his time, insisted that the provost was already well, and urged the farm hand to have a taste of the present, too. When the farm hand returned, the ache had disappeared. Later on, the provost wondered how the matter had resolved itself, and his wife revealed what she had done. The provost, of course, disapproved of his wife’s conduct, but probably was satisfied with its results – it may even be, that he was secretly convinced of the efficiency of witchcraft.

Without being well read in the legends about witchcraft, it is safe to assume that stories such as these, in which witches turn out to be cleverer than the clergy and defy their authority, are the bread and butter of said tradition. No doubt the common folk were irritated by the dominance of the clergy, which gave rise to a need to turn the hierarchy of power upside down. Tales and anecdotes were perhaps the only means the common folk had for this purpose, and what would be a more efficient subject than a witch, also coming from the peasantry, beating the priests at their own game? This need for questioning the priests’ authority is also reflected in the fact that, at least in the tales about Santala and Mutila I have come across, there is not a single one in which the priest would outsmart the witch.

According to the perhaps most gruesome story about priests and Santala, he even had a priest’s skull in his shed. Daniel Skogman, who travelled and gathered reminiscences in the Ruovesi region in the 1800s, tells how Santala collected “terrible instruments” such as “bones and snake skins”. Such instruments appear also in the tale mediated by Skogman, in which a woman resorts to Santala’s witchcraft to heal a sore eye:

Almost as soon as I entered the witch cried out in laughter. After I told him the cause of my visit, he covered my healthy eye, started then to walk around the room and curse as much as he could; then, finally, he came, banged me in the corner of my eye and said: “kohden käyköön. terveeksi tulkoon”. And I saw that much that I also felt he hit me with a skull. Cold sweat covered my body. Oh dear God, I thought, please let me get out of the hands of this brute alive; I shall never again give myself to such affairs – and that I shall not do.

The tale does not tell whether the skull in question was the aforementioned priest’s skull, nor does it reveal, if the treatment had the desired effect, but at least the conjuring made a long-lasting impression on the patient!

Presumably in a manner typical to witches, there is a supernatural story linked to the death of Santala in 1848, too. It is told that when Santala was taken to the church grounds to be buried, the trip was so long that they did not make it there before morning and the first ringing of the church bell. That was when Santala’s body started suddenly to weigh immensely. Two horses foamed when they dragged the deceased to Ruovesi church, and when they finally got there, it took six men to carry Santala in to the ground.

Ruovesi church and bell tower in c. 1910–1919. Picture: Aku Satamo (Original photo: Vapriikki Photo Archives).

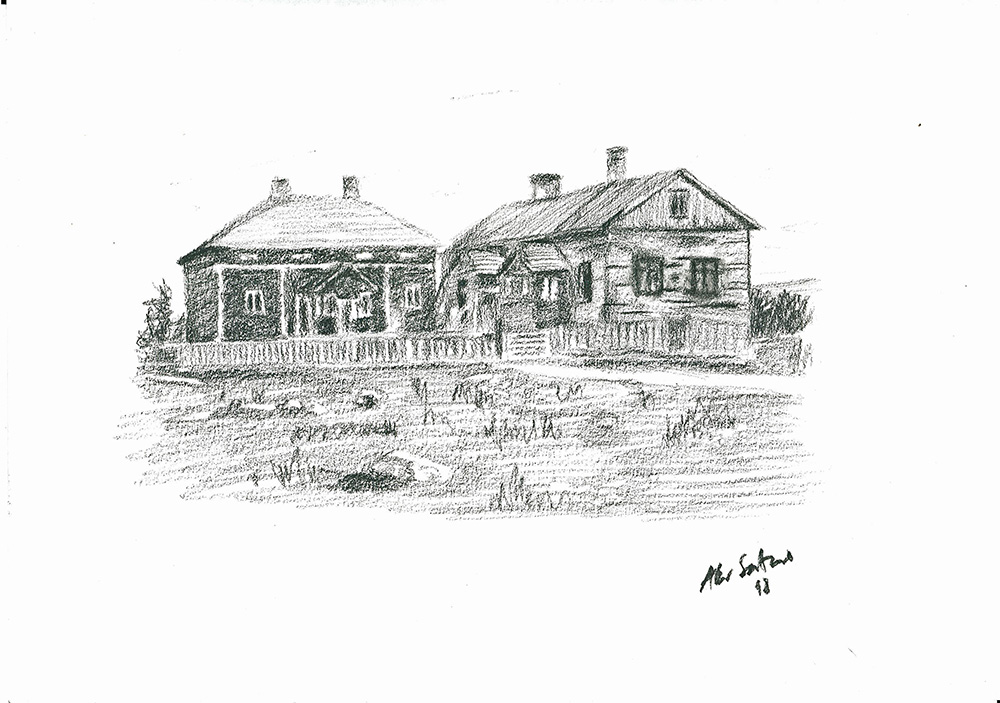

Santala’s farm is still situated by the road that leads from Murole canal to the village of Murole. The house that Santala had built for him, however, does not exist anymore: it was moved from its original place in the 1930s and finally burned down in 1949. The same fire also destroyed Santala’s large cabinet, which reputedly still contained some of his belongings. The present owner of Santala’s farm, Antti Moisio, tells that “the spruce tree of Taneli, under which his hut was situated, and an old lantern, which, according to lore, had been in that hut” are still left from Santala’s time. The hut in question was, according to Moisio, torn down by his grandfather in the 1930s. In addition to the spruce tree and the lantern, however, something else also remains: according to Moisio, there are still Santala’s direct descendants living in Murole.

The houses of Santala at the beginning of the 1900s. Picture: Aku Satamo (Original photo: Matti Luhtala / Vapriikki Photo Archives).

Matti Mutila

When Skogman was gathering his information in Ruovesi in the beginning of the 1860s, Matti Mutila was already eighty years old, but still brisk and in good form. According to Skogman, he had a “sorcery room”, which contained bottles, boxes, dried flowers, herbs, and grasses, all topsy-turvy. Mutila has been told to have been able to hypnotise his patients, and, when healing them, increased the effect of medicinal plants with incantations. Help for the mentally ill was sought from Mutila, and he had a special “mental institution” for such patients: a shed, which had a ring in the wall for chaining the patients. It is also told that church doors would open by themselves for Mutila, and that he helped to acquire a spectre of good wealth to the house of Mustanmetsä in Tyrvää. As in the case of Hetastiina Hurstinen, Mutila was said to have gotten his witchcraft from the Black Bible. However, despite his reputation as a witch, Mutila also functioned in a position of trust in his parish, and even though he was perhaps a bit feared, he was also well liked and respected.

In one story a farm-owner from Somero came to Mutila to seek help to solve the murder of his brother. According to the version of the story told in Ruovesi-newspaper by A. L., while inspecting the case, Mutila among other things “addressed some invisible spirit in a cupboard in the corner of the cabin, and the spirit answered out loud”. When Mutila went outside to continue his conjuring, the curious farm-owner looked inside the cupboard, but did not see anything else than “skulls and other magic objects”. And when Mutila returned inside and told the location of the deceased, “the farm-owner lost his mental balance so that he lost his mind”. Only after a long while did he return home as “a peculiar wretch, who did not speak or do anything sensible for many weeks”. It is hardly surprising that his brother was found in the place Mutila had disclosed.

Due to the passing of time, it is, of course, hard to say anything certain about Mutila’s skills in sorcery. But as local historian Kalervo Maunuksela has pointed out, Mutila certainly seemed to know a thing or two about the psychology of the human mind. This is demonstrated by a story – or, again, a version of it – told by Maunuksela:

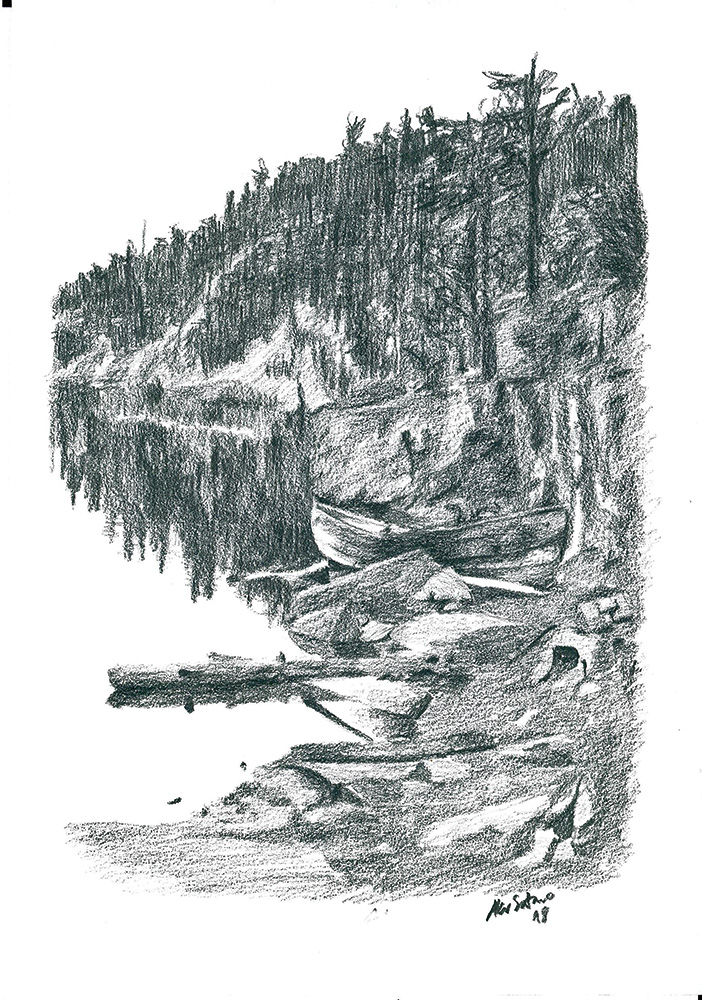

Snakes were a part of Mutila’s instruments of healing and doctoring. He might also do pranks – especially test the weaknesses of his neighbours, if he so desired. Once, coming back from Koverojärvi lake, where had been fishing, he had collected a basket full of seething adders, covered the basket with a blanket, and left it at the shore by his sauna. When he got back home, he ordered two maids, sisters Ulla and Tiina, to go and fetch the “fish basket” from the shore – but not to look into the basket, or else the fish would turn in to snakes! The girls went, but returned with “eyes overturned”.

Lake Koverojärvi in the last decade of the 1800s. Picture: Aku Satamo (Original photo: Gustin Lojander / Vapriikki Photo Archives).

The same sentiment or attitude is expressed in a story, again mediated by Maunuksela, in which a woman from Kuru came to ask Mutila for a curse on her neighbour’s fields. It is told that Mutila gave her a sack, in which she would have to gather heavy rocks, walk straight home with the sack in her back without resting or looking back, and then sow the rocks in her neighbour’s field. Maunuksela speculates that the physically burdensome task was not fulfilled, and that Mutila’s instructions were just his way to give a little snap on the fingers to the malicious woman.

Maunuksela highlights that Mutila would not consent to do harm: ”[e]verything I have done, I have done from deep goodness toward people”, he has reportedly said. In this sense he – as well as Heikki Hurstinen, perhaps Santala, too – differed from his predecessor Antti Lieroinen, who might also participate in harm-doing, although not willingly and only if absolutely so required. But Lieroinen, too, washed his hands of such matters by stating to the one demanding the deed that “on your soul I shall do this and not on mine”.

The spirit of slight pranks evident in the previous stories is also present in the tale of Mutila’s trip to Vaasa. It is told that usually, on his trips, Mutila could leave his belongings unlocked, as no one would dare to steal them. But on the said journey to Vaasa, however, one boy – perhaps not familiar with Mutila’s reputation – went to “tamper” with the fine jingle bell in his sleigh. Mutila “saw” what the boy was up to, and suddenly his fingers were locked into the jingle bell and could not be released. Calling for help was also impossible, as the boy’s “mouth was badly crooked”. The boy was thus at the mercy of Mutila, who did not hurry in setting him free – only after “letting him shiver enough” did he let him go, with an earful.

There are specific details in the story, but otherwise it sounds quite familiar – above a similar story about the inviolability of a witch’s belongings is told about Santala, too. This may be a case of a traditional tale linked to Santala and Mutila in turn, or of a tale, which was originally about one or the other, but changed protagonist as the raconteur and times changed. A similar shift may have happened also with the story about the provost’s aching finger – in the version of the story told by Kalervo Maunuksela, the conjuring and healing were done by Mutila, even though otherwise the story sounds similar to the one told above by Heikki Lammi.

So – who actually did what? This inconsistency bothered me enough to check Lammi’s original source, number 13 of the newspaper Ruovesi from the year 1921, and it turned out that it indeed was Mutila, from whom relief for the provost’s aching finger was sought. After this I read Lammi’s version of the story again, and discovered that actually he writes only of “a witch”, without naming either Santala or Mutila. Thus, I came to interpret the “witch” to mean Santala only because the text in general was about him. This is, apparently, how stories about witches get mixed!

Interestingly, the stories of Santala’s and Mutila’s deaths are also similar. Mutila died apparently in 1864, after a stroke during a church trip. In the story about his death told by Kalervo Maunuksela, his horse stopped at “Vanha Vinha” – nowadays near the start of the road leading to the Haapasaari camping site in Ruovesi – and even though his servant did his best and the horse “foamed”, it did not have the strength to pull anymore. The obvious similarities in the stories once again raise the question, whether stories about Santala and Mutila might have gotten mixed somewhere along the way – or is it typical of witches to become extremely heavy when they die?

If a modern day traveller wanted to seek advice or healing from Mutila, he/she should head toward Visuvesi from Ruovesi church, and, after about ten kilometers, turn left to Helvetinkoluntie. Along that road there is a fork in the road that would have led to Mutila’s farm. Mutila’s old cabin, as well as his “mental institute”, is, however, already gone. The same has, apparently, happened to his magical instruments, skulls, and such: one story tells that they were put in to Mutila’s coffin when he died, another claims that they were buried in church grounds by his widow, and, according to a third one, they were cast in the Mutioja brook that flows from lake Koverojärvi to lake Pohtiojärvi. While the brook was dredged in 1938, its bed near Mutila’s farm was searched, but nothing was found.

Literature and other sources

A. L. [Ahto Luutonen]: Mutilan Matti. Ruovesi 28.11.1928, 2–3.

A. L. [Ahto Luutonen]: Mutilan Matti. Ruovesi 5.12.1928, 2–3.

Hoppu, Tuomas: Entisaikojen Murole. Teoksessa Hoppu Tuomas (toim.): Kotiseutumme Murole. Ruovesiläisen kylän ja sen asukkaiden vaiheita eränkäynnin ajoilta nykypäivään. Muroleen Kylät ry 2005, 9–68.

Jokipii, Mauno: Vanhan Ruoveden pitäjän historia eräkaudesta isoonvihaan. Teoksessa Söyrinki, Niilo; Luho, Ville & Jokipii, Mauno: Vanhan-Ruoveden historia I. Vanhan-Ruoveden historiatoimikunta 1959, 75–618.

Kopponen, Tapio (toim.): Parantajat. Kertomuksia kansanlääkäreistä. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Helsinki 1976.

Lammi, Heikki: Santalan Taneli, Ruoveden suuri noita. Ruoveden Joulu 1993, 23–24.

Luutonen, Ahto: Aikaisempien aikojen muistoa Ruovedeltä. Ruoveden Sanomalehti Oy 1973.

Maunuksela, Kalervo: Mutilan noita auttoi ihmisiä. Ruoveden Joulu 1979, 16–17.

Niemi 1904.

[ei allek.]: Noidat ja rovasti. Ruovesi 30.3.1921, 4.

Ruovedeltä kerättyjä muistiinpanoja v 1861 D. Skogmanin kirjoittamasta matkakertomuksesta ympäri Satakuntaa. Suomi-kirjassa vuonna 1864. Ruovesi 27.4.1921, 3.

Sipilä, Toivo: Tyrvääläiset Ruovedellä, noituutta oppimassa. Ruoveden Joulu 1975, 40.

Other sources

Messenger-viestinvaihto Antti Moision kanssa 19.9.–4.10.2018.

Sähköpostikeskustelu Ruoveden Kotiseutuyhdistyksen sihteerin ja arkistovastaavan Veikko Önkin kanssa 19.9.–28.9.2018.

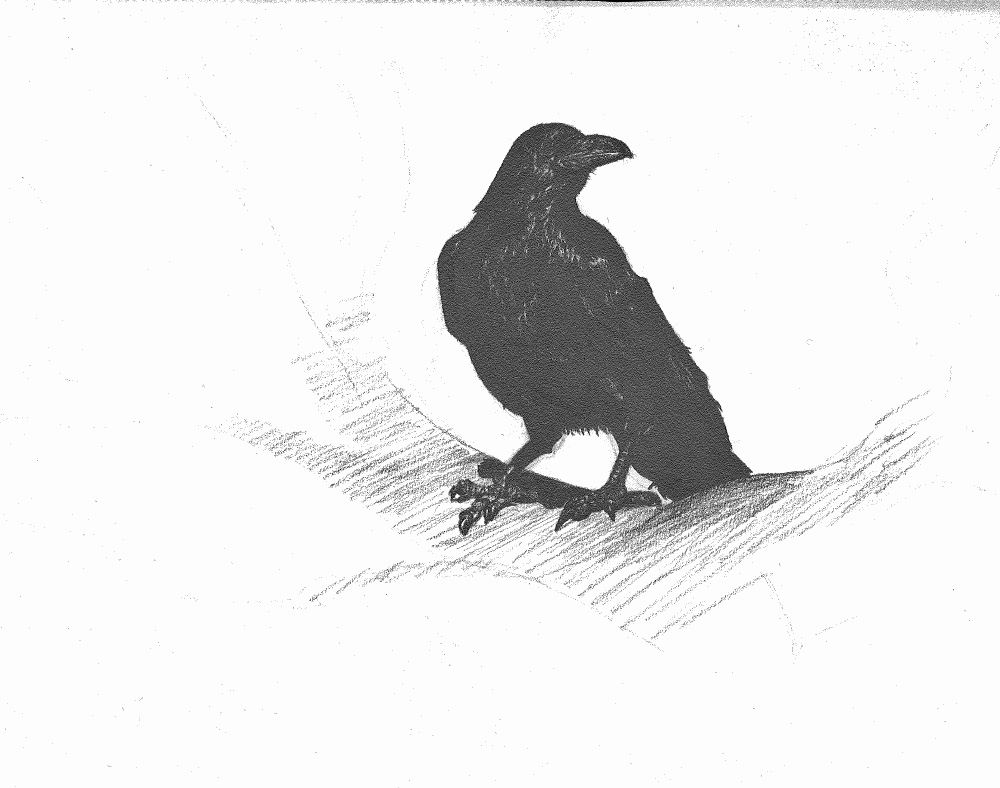

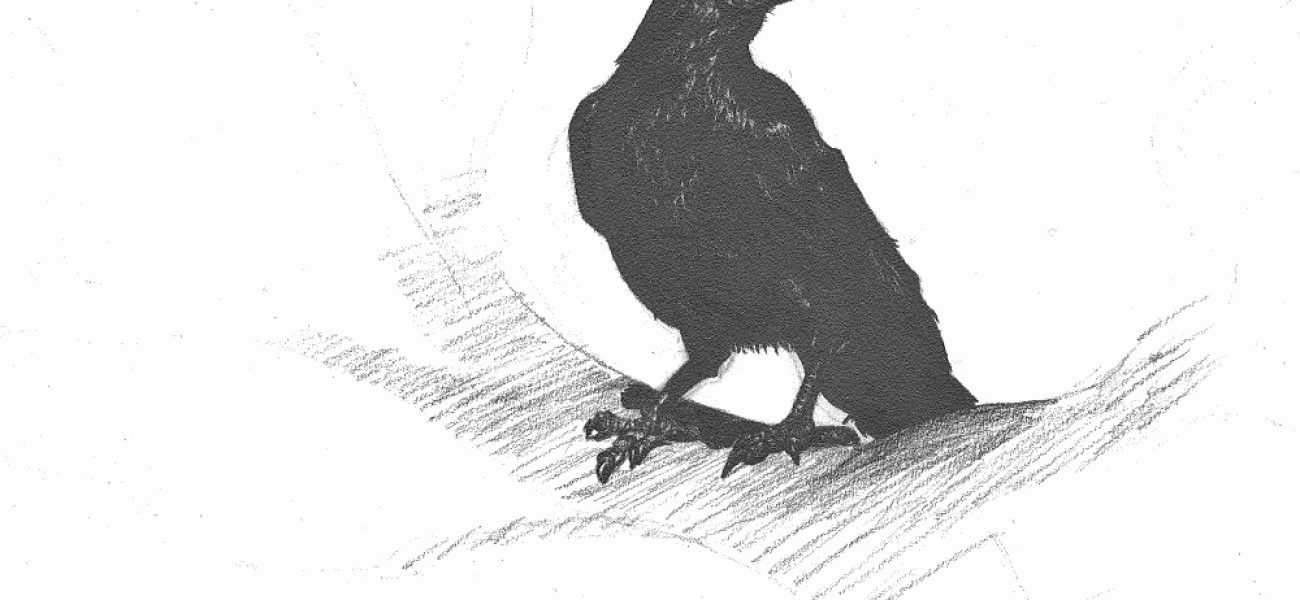

Artwork: Aku Satamo.