The most famous of the witches of Ruovesi was no doubt Antti Lieroinen, also known as Liera, who was burned at the stake in 1643. The practice of witchcraft, however, did not end with the death of Liera. In the 1800s the mighty witches Taneli Santala and Matti Mutila operated in the region, and even in the previous century – in the 1900s, that is – the famous Hurstinen sage couple were active there.

Previous witches have already become mythical beings, but of Heikki Hurstinen’s actions and thinking there is also first-hand knowledge. This is due to the work of Tapio Kopponen, who made a thorough study of Hurstinen in the 1970s. Based on personal meetings and accounts of Hurstinen’s contemporaries, Kopponen’s work (Tietäjä, 1973) offers such a rich and unique account of Hurstinen’s life, that the first part of “Supernatural Pyhä-Näsi” concentrates on Heikki Hurstinen and his wife, Hetastiina Hurstinen, and is also based almost completely on Kopponen’s work. This is because, firstly, aside from Kopponen’s book, there is apparently very little published material dealing with the Hurstinen couple, and, secondly, Kopponen’s outstanding work deserves to be raised once again into the spotlight from the oblivion of dark library vaults. So, with Kopponen as our guide, let us venture into the amazing world of the Hurstinen couple!

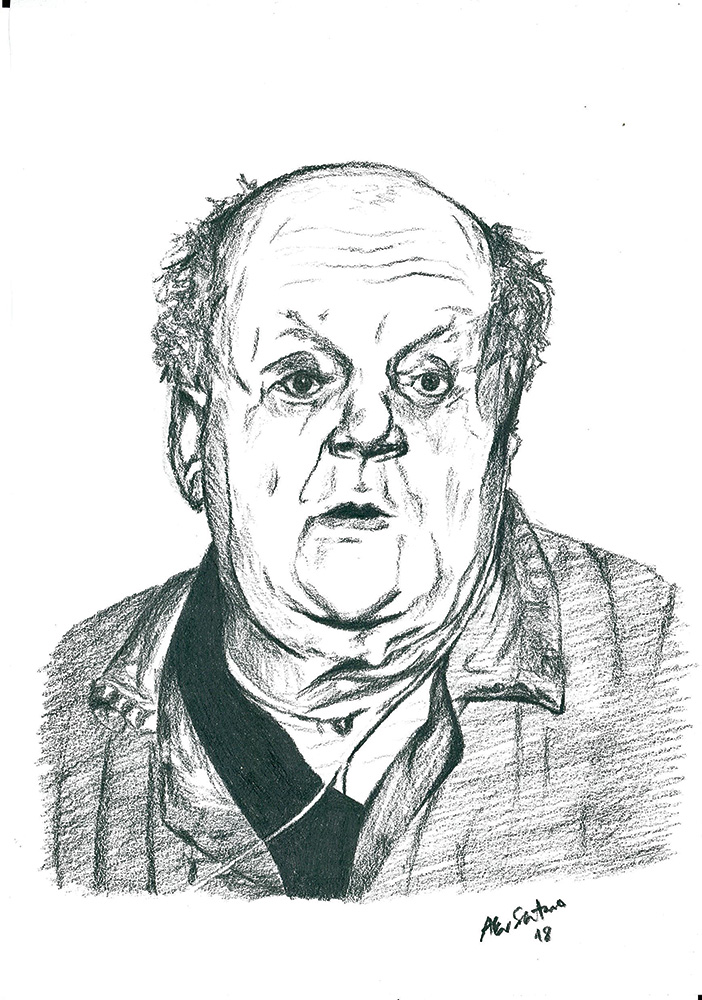

“The Electric Blacksmith” Heikki Hurstinen

– […] Power is only for helping. There have been those who have come to see me, and with money have tried to conjure evil on their neighbour – misfortunes – but those people I drive out!

– Heikki Hurstinen to Kalervo Maunuksela (Ruoveden Joulu 1972).

Heikki Hurstinen, born January 12th 1886 in the Hursti croft of Pekkala manor in Väärinmaja, Ruovesi, showed tendencies of a sage already as a young boy. Hurstinen has told that at around the age of ten, “I noticed I knew more than others, and, to my amazement, could read other people’s thoughts”. Hurstinen also healed his comrades as they were or pretended to be sick – other children, on the other hand, thought of him as a bit weird, and also made fun of him.

Hurstinen was active as a sage and healer between the years 1936–1972, and was at the top of his reputation in the 1940s and 1950s. In those years customers came to him as “an unending flow all through the year”. Even 36 persons at a time might be queuing to see him, and his clientele consisted of people from all walks of life. Hurstinen’s reputation was increased by certain cases, in which he was able to give right directions concerning the whereabouts of missing persons. In 1953 journalists even turned to him to solve the famous murder case of Kyllikki Saari. At the top of his reputation he was even fetched to Helsinki and Jyväskylä to carry out his services.

Hurstinen’s clients came to see him seeking healing, information about missing belongings and persons, or perhaps help in romantic affairs. One part of repertoire was dowsing, which he was used for even by those who otherwise would not use his services. When looking for water, he did not need a dowsing rod or other equipment, he just started trembling when the right spot had been found: “When he found a vein, he started shivering terribly. I said to Heikki that oh come on, if I can’t feel anything in my feet, surely you can’t, either. He just answered that you do not have electricity in you”, says a contemporary witness cited by Kopponen.

One of the names people used of Hurstinen was “electric blacksmith”, which stemmed from his conception of the centrality of a person’s “electricity” for his or her activity as a sage – and the fact that Hurstinen actually was a blacksmith. He had studied the profession in Ruovesi for three years at the beginning of the 1900s, and had specialized in manufacturing farm tools. Apparently, however, Hurstinen’s real talents lie in other fields – according to a contemporary he was not “the best craftsman there is, just an ordinary village blacksmith”. But Hurstinen worked as a blacksmith, too, even when being a sage had already become his main occupation.

Hetastiina Hurstinen

Even though the qualities of a sage or a shaman were apparent in Hurstinen already at a young age, he did not start his practice before the year 1936, when he was already fifty years old. The reason for this late start was, according to Kopponen, his wife Hetastiina Hurstinen – a character at least as interesting as Heikki himself.

Heikki met Hetastiina, whose surname originally was Koivunen, already as a young man, when she worked in the Hursti household. Hetastiina (30.4.1861–29.1.1936) was a quarter of a century older than Heikki, and at that time already a widow and a mother of ten children. Still, something ignited between young Heikki and Hetastiina – something that made Heikki’s father drive his son out of his house. It is claimed that the son had to leave, because the father would also wanted to have Hetastiina for himself.

Heikki and Hetastiina married when Heikki was approximately 20–25 years old –accurate data of the matter does not exist. The exact nature of their relationship is also unclear: instead of romantic feelings, their relationship may have been based on the qualities of a sage Hetastiina perceived in Heikki. Perhaps he saw him as an apprentice and a possible successor.

At the time of their marriage, in the 1910s, Hetastiina was already famous as a witch, receiving customers even all the way from Helsinki. There are a lot of typically witch-like stories of her: it is told, for example, that he got her knowledge from a Black Bible, that there was a hole behind her ear from which a cord went “into places unknown”, and that she could also harm people with her witchcraft, if she so desired. According to Kopponen, even her appearance was witch-like: “She was a tall, slim, and very dark person, who always wore black. She wore a black scarf on her head, which all but concealed her face. Her eyes looked so evil that “a lot of people flinched” when seeing them.

The creation of a mystical, witch-like aura was, apparently, also partly conscious, as Hetastiina practiced her magic openly and even exhibited her powers. There was, for example, a “device” consisting of iron balls outside her window, perhaps to assist her in her connections with the spirit world. She also drew the path leading to the lakeshore from her house with runes of a cross inside a circle, and talked using mysterious, obscure expressions. As a consequence, Hetastiina was a bit feared among locals, even though the fear might have been unfounded – according to Kopponen, Hetastiina was actually friendly, helpful, and especially liked children. A similar impression is given by local historian Kaarina Pollari: according to her, “Hetastiina is mentioned as a person, from whose door no one ever had to walk away hungry or into the night”.

Hetastiina was also known to write, and it was believed that she might have been working on a new Bible. She wrote intensively, pouring with sweat, and the toiling yielded results, too: Hetastiina left behind two laundry baskets filled with writings in beautiful handwriting. However, the person responsible for her estate inventory could not make much sense of her texts.

Part of Hetastiina’s work was also the schooling of her husband. According to Heikki Hurstinen, Hetastiina taught him by a creek in the woods, the teaching was daily, formulaic, and strenuous, and whenever there was no teaching, Heikki was forbidden to do other work or meet anyone. In other words, Heikki’s training was thorough and comprehensive, and probably one reason for the late start of his own career – he had to be ready for his future task first.

Another reason for his late start was, according to Kopponen’s interpretation, that it was not desirable to have two sages working in the same house. Such an interpretation is suggested by the close chronological connection between Hetastiina’s death and the beginning of Heikki’s active career: Heikki started his own work as a sage right after Hetastiina died in 1936. She was buried in Vilppula cemetery, and a round magical stone and a pine branch were set on top of her gravestone, the purpose of which, according to one of Kopponen’s sources, was to protect the deceased.

”It’s Not Easy”

If the schooling of Heikki Hurstinen was taxing, so was the work of a sage itself. Local historian Kalervo Maunuksela has described, how after a healing session “the blacksmith was very tired, wiping sweat even though the room was chilly, even the curtains were drawn”. “It’s not easy”, Hurstinen confessed himself, too.

Healing was thus a physically taxing procedure, but, apparently, it was even more demanding mentally. To restore his mental powers, Hurstinen had a special rite, in which he “raked” the wall of his stall with an iron rake. As a consequence of years of this “raking”, the wall was all but worn through. In addition, Hurstinen beat brooms against the wall of the stall until they broke, while making loud “growling noises”. He might also go inside the stall with his assistants, and “they would beat each other with brooms and rake the wall with an iron rake, and made “growling” noises so loud they could be heard outside on the yard”.

Kopponen speculates that this rite was designed to keep Hurstinen’s auxiliary spirits, who tried to free themselves form Hurstinen’s control, at bay. At least, according to Kopponen, a person who had taken part in the rite stated that Hurstinen “grew old and did not have the power to control the situation any more he drove the bad in himself away in this way, as they attacked the blacksmith in turn, and this way he could relieve himself”. According to Kopponen, as Hurstinen grew older, he practiced this rite more often.

Also, daily consumption of alcohol helped to keep up Hurstinen’s mental abilities. According to him, alcohol distilled out of grain helped to keep him mentally stable – sugar-based alcohol did not have the same effect. The consumption of alcohol, however, was not supposed to lead into a state of drunkenness, as that would also be harmful to the nervous system. For Hurstinen, alcohol was thus not a substance used for pleasure, but a tool to be used in his trade. It was also an essential part of the “recipes” Hurstinen prescribed: for example, an eye medicine he prescribed to Kopponen to be used orally consisted of a whipped egg added with some spirit. Local historian Kalervo Maunuksela also mentions this use of alcohol in his recollection of his visit to Hurstinen. According to him, the blacksmith “had had a few”, but was still thinking clearly. Maunuksela’s choice of words perhaps brings to mind intoxication for the purposes of self-entertainment, but his statement may also be seen to corroborate Kopponen’s view: for Hurstinen, the use of alcohol was perhaps a factor that prepared him for healing and “seeing”

The Sacred Grounds of Hurstinen

According to Kopponen, in a manner typical to shamans in general, Heikki Hurstinen had his own “shaman tree” – a spruce tree situated on sacred grounds, “the blacksmith’s grove”, as the locals called it. It was located on the other side of the road from Hurstinen’s house, circa half a kilometre away, and according to Kopponen’s speculations, consisted of a spruce surrounded by birch trees. Hurstinen went into his grove alone late in the evening or in the night, and according to one statement, a “growling” sound could be heard from the grove, apparently similar to the one heard during the “rake rite”. What Hurstinen actually did in his grove remains a mystery, as none of Kopponen’s informants could or would tell about it.

One thing that may shed a little light on the mystery is Hurstinen’s penchant for red cloth, “japonette”, which he acquired from a nearby shop, cut in squares. One of Kopponen’s informants thought that because Hurstinen continuously needed more of the cloth, he used it in his grove rites. Kopponen speculates that the cloth may have been a sacrifice, perhaps to the sacred spruce tree or a spirit in it.

Be that as it may, it is clear that the tree and the grove had a special meaning for Hurstinen. This is clearly indicated by the fact that when Hurstinen had already fallen ill, he asked a person living in his house to protect his tree – located on someone else’s property – from cutting. Hurstinen also asked the person to take him to his grove, when he couldn’t go there alone anymore. While there, Hurstinen “stood earnestly by his tree and, touched by the moment, took his hat off”. The importance of the place is also expressed by the fact that, presumably due to Hurstinen’s repeated visits, a visible path leading to the grove was formed.

Another place of importance for both Heikki and Hetastiina Hurstinen was the cemetery. Even while training to be a blacksmith, Heikki has been told to wander around Ruovesi cemetery in the evenings and nights. The same goes for Hetastiina, who, according to eyewitnesses, used to go to Vilppula cemetery to “conjure” in the evenings. According to Kopponen, this is typical of the Finnish sage tradition: the sages were thought to be capable of being in contact with the dead, from whom they also acquired their wisdom and skills. One of Kopponen’s informants actually told that when he/she went to the cemetery with Hurstinen, he told that the dead talked and encouraged to listen to them and to answer to them. Interestingly, Hurstinen implied that he could also speak with the dead via telephone – he had an extra lead going from his telephone to some kind of a hole in the ground nearby. Apparently, it was essential that the lead went underground, where the dead reside.

The Last Sage of Ruovesi?

The last years of Heikki Hurstinen’s life were marked by different ailments. He suffered from hearing loss, an expansion of the lung, and also had a stroke, even though he recuperated from it very quickly. These health issues did not, however, prevent him from practicing his profession: Kopponen tells, how Hurstinen had his own private practice in Mänttä hospital, when he was treated there. Even when Hurstinen was on his deathbed, people still came to see him with their problems.

According to Kopponen, nearing the end Hurstinen felt anxiety over the fact that he hadn’t found a successor for his work. He saw himself as a part of a chain of sages, which, come his demise, was in danger of breaking., which is perhaps best exemplified by his trip to Lieransaari in Ruovesi – the place where the witch Antti Lieroinen was reputedly burned at the stake – to honour and “address” his most famous predecessor.

Kopponen himself also speculates with the possibility of the Hurstinens being a part of the long continuum of Ruovesi sages and witches – that their wisdom and skills would stem directly from the previous sages of the locality. Unfortunately, the only information of how Hetastiina was taught her witchcraft, seems quite myth-like: according to Kopponen’s source, “she was taught by a spirit in a deep gorge in the woods”. Still, Kopponen notes that there is a chronological connection between Hetastiina Hurstinen and her predecessors. When she was born in 1861, the previous great sage of Ruovesi, Matti Mutila, was eighty years old. Mutila, however, died only a few years later, and thus the thought of him teaching Hetastiina doesn’t seem very convincing – unless we take into account the possibility that the spirit, who taught Hetastiina in the gorge, was Mutila’s. This is, at least, how writer Matias Riikonen tells the story in his novel Suuri fuuga (2017).

In spite of the lack of concrete evidence, Kopponen sees that “it would seem natural to assume that Hetastiina is somehow connected to the sage tradition of Ruovesi”, which would also mean that Heikki Hurstinen would be the “last link in the mighty series of Ruovesi sages”. This is undoubtedly an important observation for understanding Heikki Hurstinen’s thinking: if the Hurstinen couple really possessed information that had been passed on from one sage to another during the ages – or if that is what they thought – the anxiety Heikki Hurstinen felt over the issue of his successor becomes easy to fathom.

According to Kopponen, Heikki Hurstinen had several candidates to continue his work, but there was something in each of them that prevented them from becoming a proper sage: one of his students received the required knowledge, but did not have enough “electricity” needed for the job – on the other hand, one person who had the required electricity, was not in the least interested in becoming a sage. Finding a successor was thus difficult, as both knowledge and tendency were required. Just receiving instruction from Hetastiina would not have been enough in Heikki’s case, either, as the natural propensities he showed from a young age were an essential factor, too. Heikki himself recounted how he had gotten his own “power” from his mother.

A suitable successor was never found, and after Hurstinen died in March 1972, he was buried in Vilppula cemetery, under the same gravestone as Hetastiina. Apparently, the grave can still be found, even though the magical stone and pine branch on top of the gravestone are there no more. Also, the house of the Hurstinen couple still exists and is situated in the vicinity of Vilppula prison along the Patruunan polku route of Pyhä-Näsi. However, to respect the privacy of the present owners of the house, we will not reveal its exact location here.

Hurstinen’s sacred spruce and grove might also still be found, at least in theory: as previously stated, the path to Hurstinen’s grove started from the front of his house, and the grove was situated a half a kilometre from there. Whether the grove or the spruce have made it to present day, is, however, difficult to say – the path leading there has presumably already disappeared due to lack of use. But if, when wandering in the woods of the area, one happens to find a frail piece of red cloth at the feet of a spruce tree, that is a sign of being at the sacred grounds of the last sage of Ruovesi.

LITERATURE:

Kallio, Jaana: Jäähdyspohjan historia. Antti Lieroinen. Jäähdyspohjan kyläyhdistyksen sivut (http://www.jaahdyspohja.net/historia/lieroinen.html). Julkaistu 2005, luettu 9.10.2018.

Kopponen, Tapio (toim.): Parantajat. Kertomuksia kansanlääkäreistä. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Helsinki 1976.

Kopponen, Tapio: Tietäjä. Heikki Hurstisen toiminnan tarkastelua. Helsingin yliopiston Kansanrunoustieteen laitoksen toimite 4. Suomen Kansantietouden Tutkijain Seura, Helsinki 1973.

Maunuksela, Kalervo: Seppä Hurstinen ”katsoi” missä kadonneet ovat. Ruoveden Joulu 1972, 19–21.

[ei kirjoittajatietoa]: Teiskon mies tulee hakemaan parannusta seppä Hurstiselta. Vilppulan Joulu 1981, 40–41. Julkaistu alun perin teoksessa Virtaranta, Pertti: Suomen kansa muistelee [WSOY, 1964].

Pollari, Kaarina: Vilppulan kirkkomaa, sen muistomerkkejä ja ihmisiä niiden takaa. Teoksessa Kemppainen, Raimo (toim.): Vilppulan hautausmaa ja kirkot. Vilppulan seurakunta 1994, 49–112.

Riikonen, Matias: Suuri Fuuga. Into Kustannus 2017.

Artwork: Aku Satamo.